Vue d’exposition (photo Philippe De Gobert)

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Fernand Léger, 2014

Photographie NB marouflée sur aluminium, 110 x 88 cm. Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be American Indian (Warhol’s Russell Means), 2005

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 74,5 x 91,5 cm

Vue d’exposition (photo Philippe De Gobert)

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Arafat, 2010

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 110 x 90 cm. Edition 5/5

Vue d’exposition (photo Philippe De Gobert)

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Frida, 2005

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 105 x 128 cm. Edition 5/5

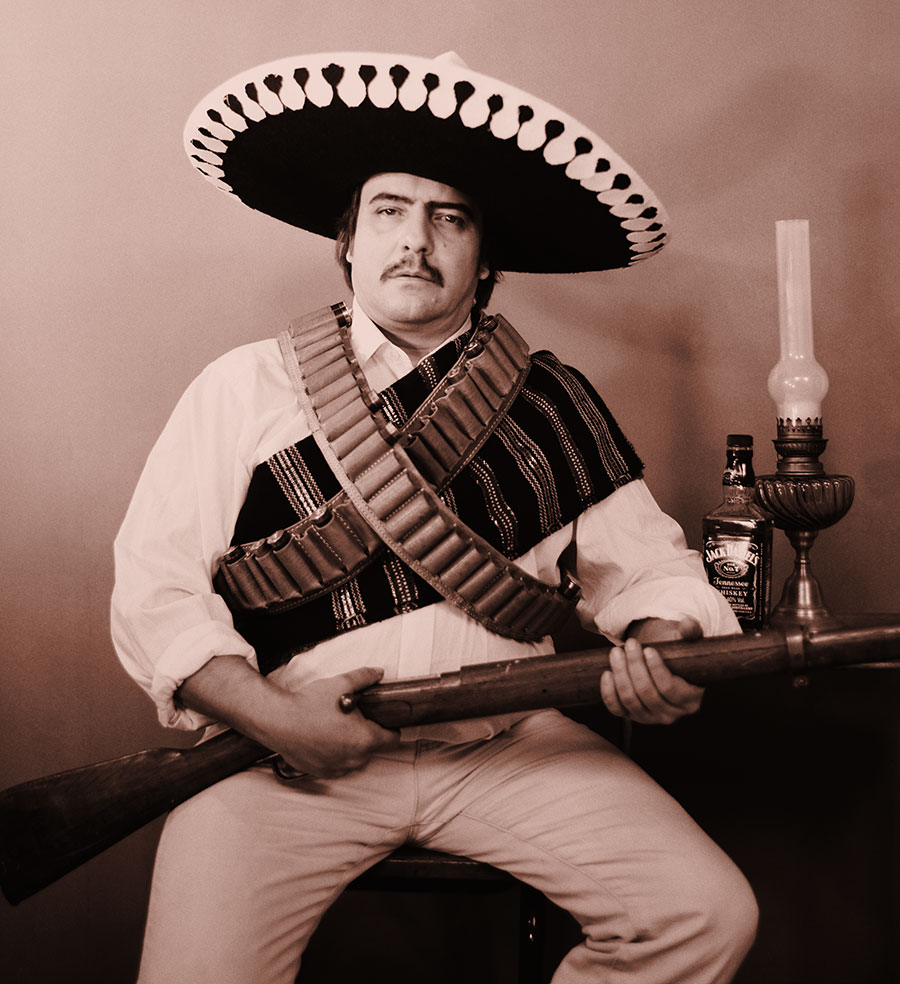

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Pablo Escobar en Pancho Villa, 2014

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium

Edition 5/5

Vue d’exposition (photo Philippe De Gobert)

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Che, 2001

Photographie N.B marouflée sur aluminium, 75 x 75 cm. Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Dutroux, 2009

Concept & performance : Emilio López-Menchero, portrait de commande de Laurent d’Ursel, costumes, accessoires : Hélène Taquet photo : Annabelle Guetatra, Hélène Taquet & Emilio López-Menchero.

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 79,5 x 63,7 cm, 2009. Edition 5/5.

Since the early 2000s, Emilio López-Menchero has been regularly trying out different incarnations: appropriating the fascinating gaze of Pablo Picasso (2000); inhabiting Rrose Selavy (2005); substituting himself for Harald Szemann (2007); incarnating Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame, Russell Means style (2005); laying bare Rodin’s Monument to Balzac (2002); changing sex and composing a Frida Kahlo with herself as the subject (2005); taking on Rasputin’s hieratic pose (2007); conquering the Christ-like face of Che Guevara (2001); wearing Arafat’s keffiyeh (2009); turning himself into Carlos the Jackal, terrorist and master of cunning and disguise (2010); posing like Fernand Léger (2014), who also swapped the architect’s drawing pen for the painter’s brush. What motivated Emilio López-Menchero to attempt these successive incarnations, some 20 in all? After he shot his self-portrait of Pablo Picasso bare-chested in boxer shorts (2000), based on a photograph taken in the artist’s studio in Rue Schoelcher in 1915 or 1916, he said that the challenge was all about recreating this photographic self-celebration, of both his body and his artistic genius, which is something Picasso did regularly. The aim was not to create a pastiche of the photograph, or to imitate Picasso, but to incarnate both this ‘painter being’ and the archetype of the virile, macho Spaniard. Through these references, the artist initiates a process of reflexivity and recreation, mixing the familiar and the unfamiliar, recognition and surprise, erudition and facetiousness. A somewhat eccentric, even extravagant transformer, while changing his identity, López-Menchero finds his own. ‘Being an artist,’ he says, ‘is a way of expressing your identity; it’s the act of constantly inventing yourself.’ Each piece is unique, each Trying to be (the title of the series) is a specific adventure, an existential construction composed of autobiographical elements, references to other artworks, self-depiction, and a reflection upon the signals given out by the icon he has envisaged in detail. Ultimately it is self-construction via a continuous reflection on identity and its hybridities, exploring certain myths, their lies and their truths. The artist offers up a combination of exposure, disguise and domestic heroism. ‘Every true artist is a naive hero,’ wrote Émile Verhaeren of James Ensor, whose portrait in a woman’s hat with flowers and feathers Emilio López-Menchero revisited (2010). A naive hero is exactly what he is. On this topic I am reminded of the letter André Cadere wrote to Yvon Lambert in 1978, just before his death: ‘I would also like to say about my work and its multiple realities that there is another fact: the hero. You could say that the hero is in the midst of people, among the crowd, on the pavement. He is a man exactly like any other. But he has a conscience, maybe a way of seeing that, somehow or other, allows things to come to the fore, almost through a sort of innocence.’ This is a very accurate definition of artistic practice: it applies just as much to Emilio López-Menchero who, moreover, incarnated André Cadere (2013), carrying on his shoulder one of the Romanian artist’s round bars of wood, inspired by a now famous photograph taken by Bernard Bourgeaud in 1974. I would add that heroism can indeed be domestic: proof of this lies in the film that Emilio López-Menchero called Lundi de Pâques (Easter Monday, 2007), a ‘making of’ video of his Trying to be John Lennon, inspired by the Let it Be album cover. This film, made with a low budget, which gives it an undeniable intimacy, is a long series of almost pathetic attempts to pose as and inhabit Lennon in a private, homely setting that is strikingly realistic. Here, Trying to be becomes LET ME BE, while Easter Monday is an unusual day, a day, a new day, a regenerative metamorphosis.

Emilio López-Menchero simply had to appropriate Man Ray’s famous photo of Marcel Duchamp dressed as a woman – the identity photo of Rrose Selavy, ‘stuck up and disappointing’, the artist’s ‘alter ego’, Duchamp’s ‘Ready Maid’. Trying to be Rrose Selavy (2005) is the archetype of the genre, in this case a change of gender. Similarly, it was in some way expected, or understood, that he would also incarnate Cindy Sherman (2009). Since her earliest works over 30 years ago, the American artist has almost exclusively used herself as her model and the basis for her compositions. Examining identity, a frenetic need to reproduce her ‘me’, her work represents the ultimate challenge of deconstructing genres, using farce, theatrics and hybridisation. Emilio López-Menchero chose one of Cindy Sherman’s Centerfolds from 1981. These horizontal images, like the double-page spreads in fashion and girly magazines, were commissioned by Artforum but never published, because the editor of the famous art journal believed they reaffirmed too many sexist stereotypes. The American artist – and therefore Emilio López-Menchero as well – is depicted as a vulnerable, fragile woman with no means of escape, held captive by the gaze of others.

Like Cindy Sherman, the Trying to be compositions are mostly photographs rather than videos. Emilio López-Menchero transforms himself with make-up, costumes and accessories. He carefully monitors every aspect of the process, down to the tiniest detail. But the most important thing is the pose – to make his pose as close as possible to the icon he is referencing, but while completely reappropriating it in his own personal way. Mostly, these transformations are based on documentary research, which often guides the process of (re)creation. For example, in the portrait of Balzac in braces – photographed by Bisson in 1842 and owned by Nadar – the Napoleon of the arts has his hand on his heart. When the artist discovered it, the chance of possibly being able to reproduce his physiognomy was what motivated him. At the same time, he was looking at photos of Rodin’s Monument to Balzac taken by Edward Steichen, and various preparatory studies made by Rodin, which led him to the sculpture of Balzac itself. In fact, this duplication, of the sculpture and its photographic avatars, and of the physiognomy of Balzac and the work by Rodin, condenses the process of incarnation he is undertaking. That process ended up as the exhibitionist work that lays bare not only Rodin’s magnificent sculptural gesture, but the artist’s body as well. Exhibiting nudity and virility, López-Menchero strips back the process of synthesis conducted by Rodin, who sculpted the author’s naked body before covering it with a monk’s cowl. He is now as authentically Balzac as Rodin’s sculpture.

To personify Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, he does not choose one of her numerous self-portraits; instead he uses a photograph by Nickolas Muray, entitled Frida on White Bench, taken in 1938, which is both a frontal portrait and a composition. It is the political and cultural manifesto for an autonomous Mexican culture that interests Emilio López-Menchero. The intimate, the artistic, and social and political engagement transfigure Frida, who said that she often painted portraits of herself because she was the person she knew the best. When it was recently suggested to him that he incarnate Fernand Léger, he set his sights on a photo taken in 1950 by Ida Kar, a Russian photographer of Armenian heritage, who lived in Paris and London. Ida Kar took numerous portraits of artists and writers, including Henry Moore, Georges Braque, Gino Severini, Bridget Riley, Iris Murdoch and Jean-Paul Sartre. With a cap jammed on his head, and a salt-and-pepper moustache, Emilio López-Menchero stares down the lens, sitting astride a chair, his elbow resting on its back – a pose that Fernand Léger liked to assume. Reinhart Wolff and Christer Strömholm photographed him in the same pose. Once again, as in many of his Trying to be portraits, Emilio López-Menchero seeks to capture Fernand Léger’s gaze – a gaze full of curiosity for all forms of modernity.

Within this series of portraits – these self-portraits, these reiterated attempts to put himself inside the mind of the model – his Trying to be James Ensor (2010) occupies a unique place. Ensor painted images of himself throughout his career: he left behind over 100 self-portraits. ‘In his early paintings, he appeared young, dashing, full of hope and spirit, at times sad but still splendid,’ wrote Laurence Madeline. ‘Soon, however, he vented his rancour by subjecting his image to a number of metamorphoses. He became a May bug, he declared himself mad, he “skeletonised” himself. He identified himself with Christ, and then with a humble pickled herring. He caricatured himself, made himself look ridiculous… He was both puppet master and puppet, in comedies and tragedies.’ Among these self-portraits is one in a flowery hat from 1883–1888, in which James Ensor modelled himself on Peter Paul Rubens. James Ensor ironically swapped the master’s hat – with panache – for a woman’s hat with flowers and feathers. ‘In these times, when anyone is everyone, the poet, the painter, the sculptor and the musician is only worthwhile if he is authentically himself,’ Emile Verhaeren said of the baron from Ostend. This self-portrait in a woman’s hat is a sort of Trying to be avant la lettre: clearly, he could never have escaped the Emilio López-Menchero treatment.

[sociallinkz]