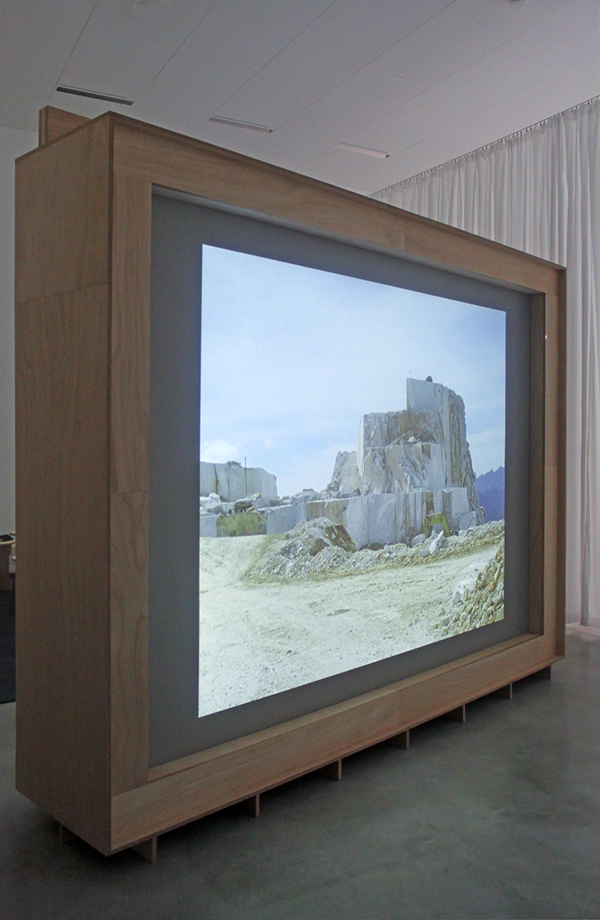

Concrete & Samples III Carrara

16 mm transferred to video, color, 4:3, no sound, BE/AT, 2010, 19′. Image Sébastien Koeppel. Editing Aglaia Konrad, Fairuz. Colorgrading Sébastien Koeppel. Produced by Auguste Orts

(…) One is reminded here of the work 19th-century architectural philologists like Karl Botticher, whose The Tree Worship of the Greeks (1856) argues that trees, forests, rivers, rocks, and mountains were the first « image signs » of the gods and functioned as their first « temples. » These natural elements had a hybrid ontological status: they served both as the object and the space of worship; they were indiscriminately the incorporations as well as habitations of the gods. Any form of tectonic structure was attached to these animate bodies of nature.

The preeminent 19th-century architect Gottfried Semper coined the term « pre-architectonic » (vorarchitektonisch) to describe tectonic formations of the « earliest times » (preceding the civilizations of Assyria and Egypt), in which large architectural monuments are not yet present. One may discover such a « pre-architectonic » state either in artefacts like pre-historic pottery and weapons, but also in nature itself, as Botticher’s description of the tectonic properties of trees demonstrates. Geologists in the 19th century, like Charles Lyell, would describe the geological stratification of the earth in tectonic terms, just as physicists like Georges Tyndall would write about the architectural capacities of water, evident, for example, in icebergs and glaciers. Carrara, as filmed by Konrad, is the site of such a « pre-architectonic » condition, not because it provides the material source for architecture, but because it constitutes an entrance to architecture through the tectonics of nature and its elaborate mineral formations. Animation in Konrad’s Carrara consists of the reciprocal movement between architecture and pre-architecture. The film runs along the gap, simultaneously tectonic and ontological, between the two conditions. Konrad’s essential contribution to a history of architecture with this film is not an account of the exploitation of a geological site as a material resource for building purposes, but the presentation of an alternative scenario of the stone’s own tectonic activity beyond human intervention. The film makes one rethink what the architecture of the stone itself could have been if it were left alone to continue building its own « slow » structures. Would it continue to produce « earth pyramids »? Or would it re-channel its capacity for mimicry to the non-manmade or « pre-architectonic » inorganic? (…) (Spyros Papapetros)

Aglaia Konrad

Concrete & Samples I Wotruba Wien

16 mm transferred to video, color, 4:3, no sound, BE, 2009, 13’37. Image Vincent Pinckaers . Editing Aglaia Konrad & Fairuz. Colorgrading Sébastien Koeppel.

Produced by Auguste Orts

(…) It is telling that Konrad’s Carrara film is the third in a tripartite series of short films with the general title Concrete & Samples. The first two films of the trilogy are monographs, so to speak, of two individual buildings, specifically two church buildings made of concrete. The first film, subtitled Wotruba Wien (2009), portrays the Church of the Highest Holy Trinity (Kirche Zur Heiligsten Dreifaltigkeit), built between 1974 and 1976 on top of a hillside in Vienna-Mauer, after the designs of (or « envisioned by, » per the film ‘s end credits) the Austrian sculptor Fritz Wotruba. The second is subtitled Blockhaus (2009) and records another monumental concrete building, the church of Sainte-Bernadette du Baulay in Nevers, France, designed by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio (1963-1966). What is the connection between these two concrete church buildings and the marble site of Carrara? Contrary to the marble used in buildings since antiquity, concrete is a synthetic compound that does not emerge organically from the ground and has a much shorter timeline in the development of human building. However, after a century of extensive use in modern architecture, concrete bas acquired a layered history perhaps equally dense in cultural and socio-political content as the Carrara marble. Both of these two concrete church buildings are prominent chapters of this tectonic history-less heroic than the first, perhaps, but no less charged.

A further affinity among all three films of this trilogy is based on the implicit mimicry of the materials these buildings are made of. Konrad presents concrete as an inorganic compound that strives to re-organicize itself. She records the material properties of two concrete structures that are now over forty or fifty years old and, consequently, have begun to show obvious signs of aging and animate growth: cracks, molding, widespread erosion, etc. Moreover, in the Wotruba Wien film, this inorganic mimicry expands to the tectonic properties of the material. Konrad’s camera focuses on the way that the church’s over one hundred and fifty concrete blocks are assembled into asymmetric piles with intensely cantilevered projections, as if they were geological formations created over time by natural forces or mere accident. If gravity seems to undermine rather than reinforce the cohesiveness of this precarious assemblage, what holds these stones together?

In its emulation of similar pre-architectonic assemblages of stones, which, in some of Konrad’s frog’s -eye views, evoke the Stonehenge pillars in size, Wotruba’s concrete envelope also implies the reanimation of a social enclosure consolidated (and here consecrated) by the gathering, not of the pious faithful, but of these riotous slabs. In fact, unlike the subtle presence of humans in Konrad’s Carrara film, there are no human visitors in Konrad’s two concrete films. And yet the spaces appear by no means empty, as the sociability of humans bas been replaced by the material sociation of stones, concrete slabs, and vegetables performing their own ritual gatherings. In this church, the « Highest Holy Trinity » consists of grass, glass, and concrete.(…) (Spyros Papapetros)

Aglaia Konrad

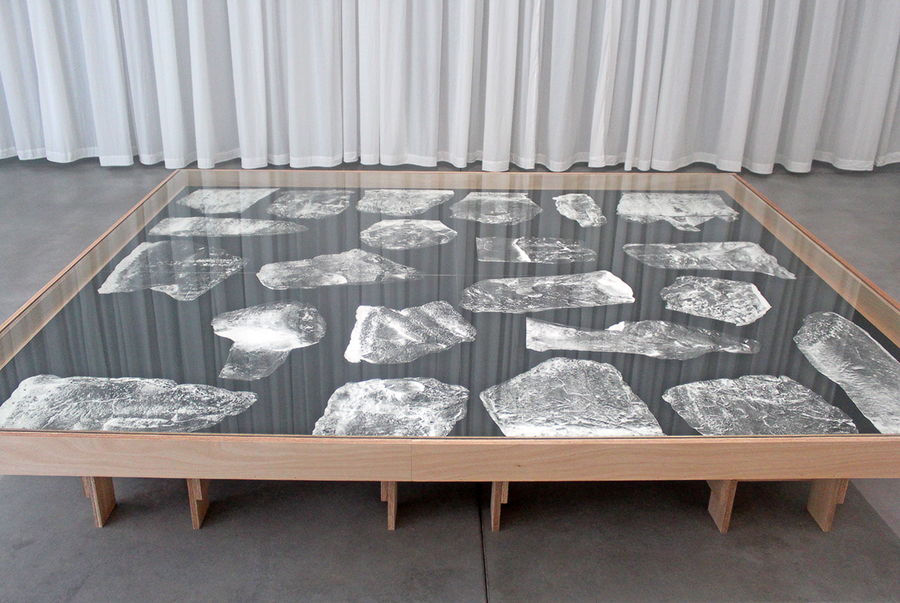

Full Circle Avebury, 2016

Epreuves à la gélatine argentique sur papier baryté.

Aglaia Konrad met littéralement à plat les pierres dressées du site néolithique d’Avebury dans le comté du Wiltshire, constitué de plusieurs ensembles de mégalithes d’une ampleur exceptionnelle, un immense cromlech qui entoure un village du même nom et deux autres cromlechs plus petits. La mise en page de ses épreuves imprimées sur papier baryté s’apparente aux anciens inventaires des archéologiques, un corpus minéral antédiluvien. Aglaia Konrad nous invite à faire le tour complet de ce cercle de mégalithes qu’elle a déconstruit.

[sociallinkz]