Jacques Lizène

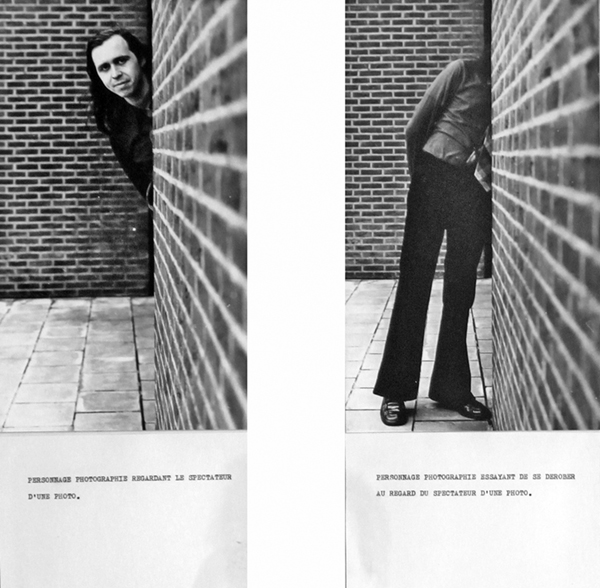

Personnage photographié regardant le spectateur d’une photo. Personnage photographié essayant de se dérober au regard d’un spectateur d’une photo, 1971

Collection privée

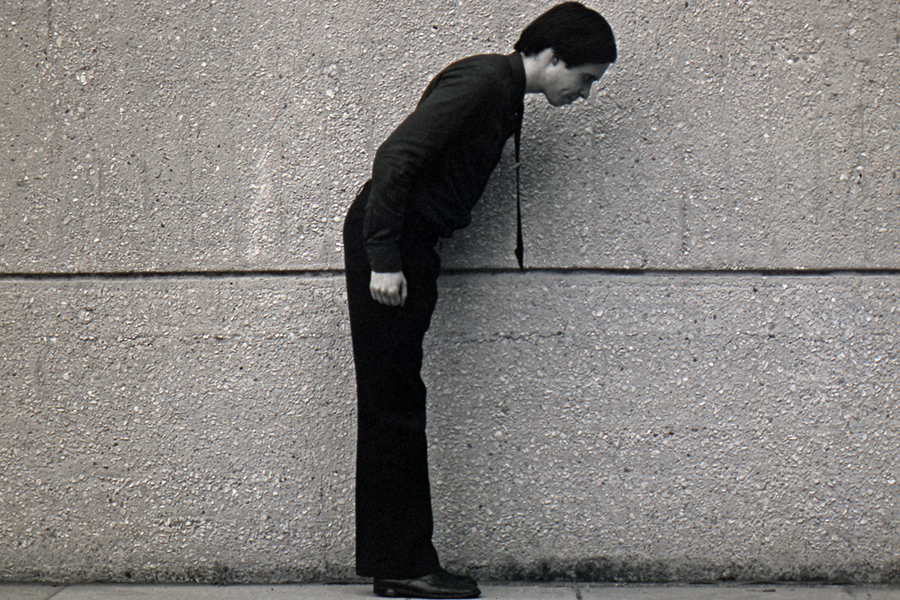

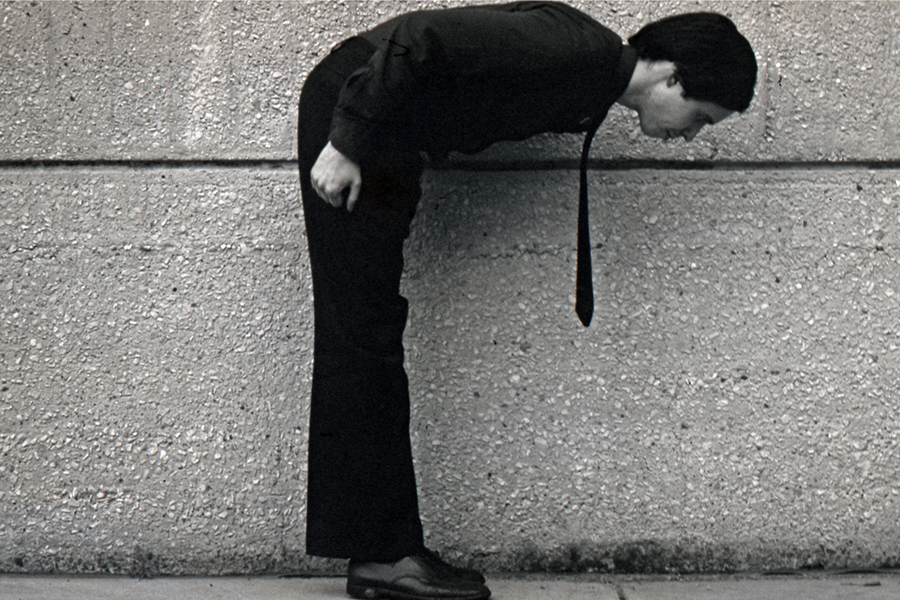

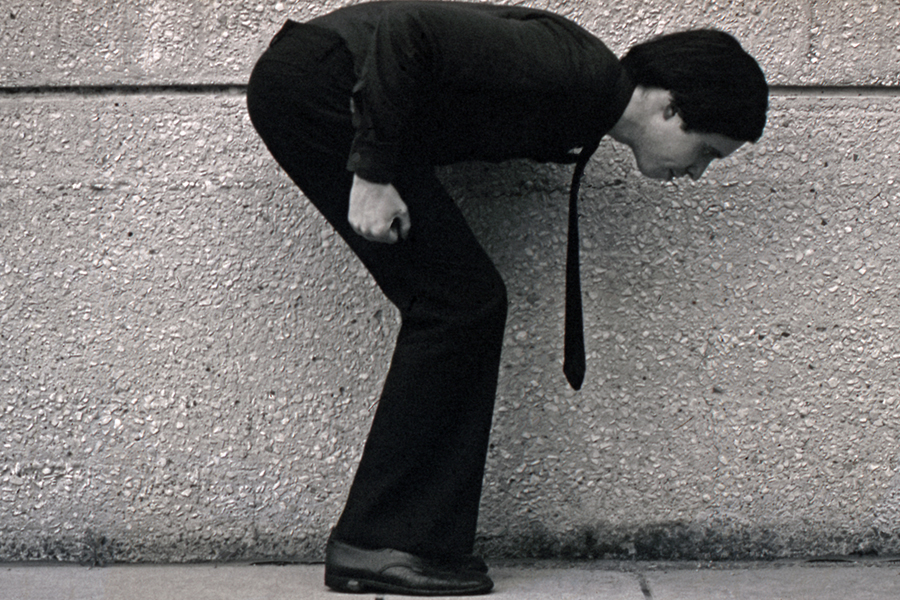

Jacques Lizène

Contraindre le corps à s’inscrire dans le cadre, 1971

7 diapositives produites par Yellow Now

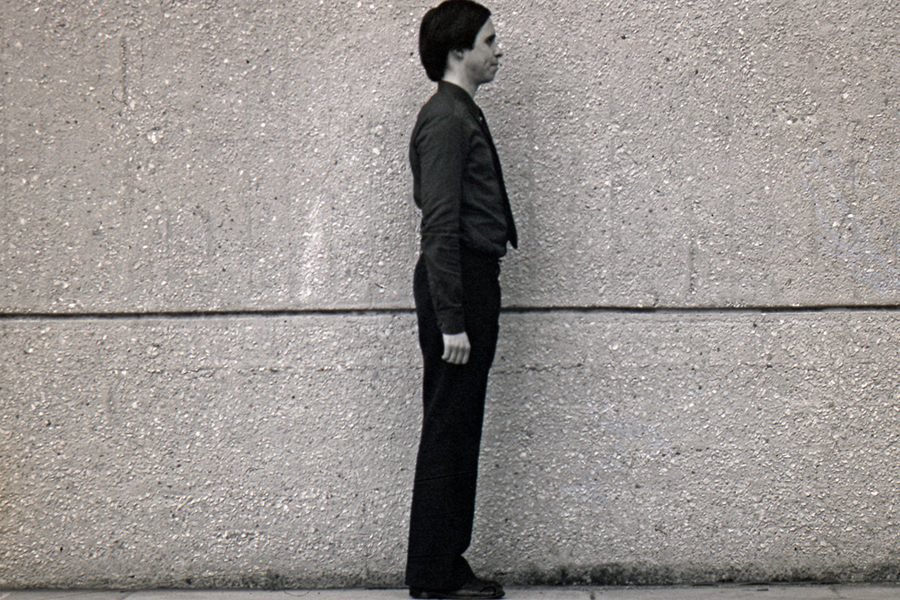

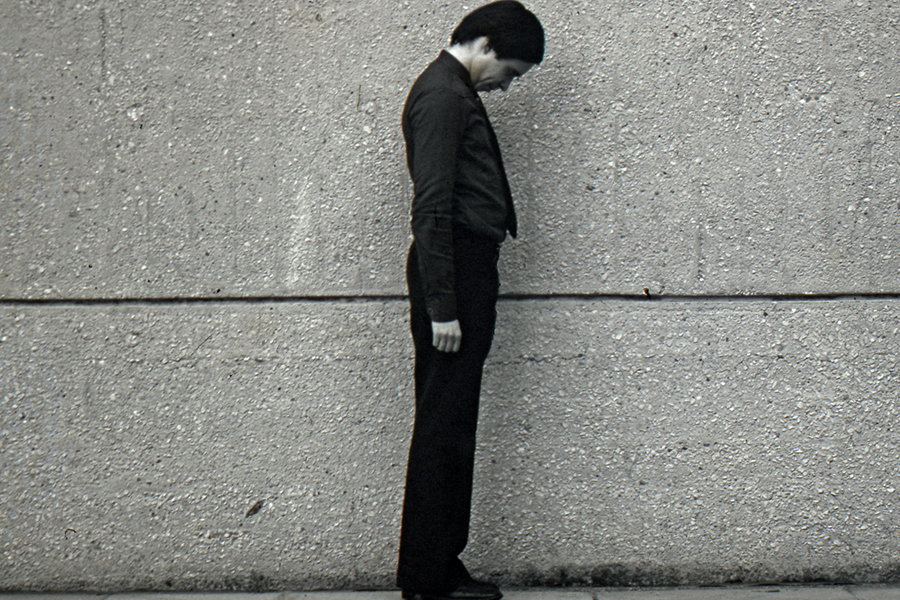

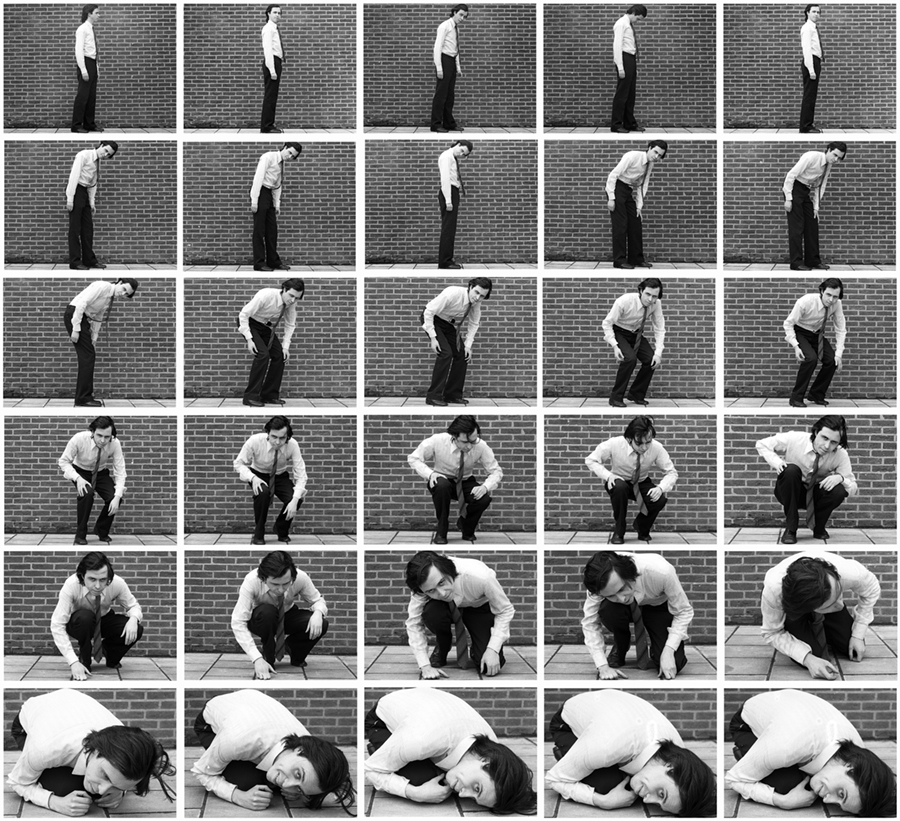

Jacques Lizène

Contraindre le corps à s’inscrire dans le cadre de la photo, 1971.

Suite de 30 photos NB, tirages argentiques, 76 x 89 cm

Lu dans : Liesbeth DECAN, Conceptuel surréaliste pictural. Photo-Bases Art in Belgium (1960s-early 1990s), Leuven University Press, 2016

(…) Right after the Specific Art exhibition, Lizene created a group of photographic works in which he executes certain actions underlining his distinct medium-specific approach. The pictures are all inextricably bound up with their titles, which describe the absurd performances represented in the pictures. The picture frame is the photographic feature Lizene focused on most in these works. For instance, Forcing the Body to Fit Inside the Photo Frame [Contraindre le corps a s’inscrire dans le cadre de la photo] (1971) shows a mosaic of thirty self-portraits that gradually picture the change from a standing to a kneeling position. (fig. II.9) In each image, the camera zoomed closer and closer to the subject, forcing him to bend down increasingly until he appears totally contained by the framing of the camera. Visual links between this work and examples from the international art scene can be found in Sol Le Witt’s Schematic Drawingfor Muybridge II (1964). Le Witt presents a sequence of images that requires the viewers to move their body in response to the work. An early photo series by Robert Rauschenberg, entitled Cy +Roman Steps (1952), shows the legs and finally the torso of his friend, the American painter Cy Twombly, approaching the camera frame-by-frame. All three of these works document the idea of temporality through an incremental sequence of body movements-made either by the subject or the viewer. (Osborne, 2002: 56) Apart from the fact that Lizene does the performance himself, there is another striking difference between Lizene’s works and those by LeWitt and Rauschenberg: by cutting off the face of the individual, Le Witt and Rauschenberg do not allow the insertion of emotion or expression. This lack of emotion or expression as well as the suppression of authorial subjectivity, are characteristics often found in Conceptual art. By contrast, in the case of Lizene, who looks and smiles at the camera, the work operates as a type of self-interrogation, through which the artist puts his action into perspective.

Other, related works from 1971 include: Minor Master from Liege Having Attached His Tie to the Photo Frame [Petit Maltre liegeois ayant accroche sa cravate au cadre de la photo] (fig. II.10), showing a full portrait of theartist whose tie indeed seems to be attached to the right upper corner of the photograph; Minor Master from Liege Entering the Frame of a Photo [Petit Maitre liegeois s’introduisant dans le cadre d’une photo], in which the artist pops up in the right part of the picture merely showing the upper part of his body; Minor Master from Liege Joyously Entering the Frame of a Photo [Petit Maitre liegeois s’introduisant joyeusement dans le cadre d’une photo], which consists of a sequence of two photographs showing the artist entering the frame of the picture while smiling; and Minor Master from Liege Hesitating Before Entering the Frame of One Photo or the Other [Petit Maître liegeois hésitant à entrer dans le cadre de l’une ou de l’autre photo], which includes two photographs, the frames of which cut the portrait of the artist in half. Two last examples within this group even more explicitly make clear Lizene’s interest in a medium-specific inquiry: Specific Photographic Art: A Walk Around the Frame [Art specifique photographique. Promenade autour du cadre] and Specific Photographic Art: Figure in the Corner of the Photo [Art specifique photographique. Personnage s’inscrivant dans le coin de la photo]. The former is composed of cut frames from a roll of color film, arranged in a rectangular shape so that the figure in the images walks around ; rectangular. The latter is a slide, which shows Lizene sitting indeed in the corner of the photographic image.

The performance aspect – typically executed by the artist himself-links this group of works to the « Conceptual canon, » more precisely, to « California Conceptual art » with Bruce Nauman as a key figure. According to Jeff Wall in his essay « Marks of Indifference, » mentioned above, the performative qualities of Nauman’s work « brought photography into a new relationship with the problematic of the staged, or posed, picture. » (Wall, 1995: 253) Furthermore, Wall described Nauman’s performances as a manifestation of the « subjectivization of reportage » within the realm of Photoconceptualism. (ibid.) In his view, Nauman’s studio photographs, such as Failing to Levitate in the Studio (1966) or Self Portrait as a Fountain (1966-67/70), changed the terms of classical, studio photography into a mode that was no longer isolated from reportage. Nauman realized this by working within the experimental framework of performance art, executing « a self-conscious, self-centered ‘play. »‘ (Wall, 1995: 254) Wall also added that it is as if Nauman’s color photographs go back to « the early ‘gags’ and jokes, to Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, to the birthplace of effects used for their own sake. » (Wall, 1995: 254)

Building on Wall’s analysis and further investigating Nauman’s early photographs, John Roberts concluded that « to enact something as an event for the camera, something as banal as spitting out a fountain of water, is not merely to produce a photograph of a ‘performance’ but to opt for the possibility that photography might have established a very different relationship to the ‘real’ than conventionally supposed. » (Roberts, 1997: 27) « They disrupt, » he continued, « in casual, humorous and at times inane ways, the privilege given to certain high-serious identities in art and photography, in particular the idea of the anonymous author in Modernism (as a rejection of the bad-form of self-description and autobiography) and the idea of the photographer as objective witness. » (Roberts, 1997: 27-28)

Although Lizene’s photographs were not made in the st udio (but certainly could have been), his work corresponds to these analyses. Lizene is also the subject of a « self-centered play » that uses the strategies of reportage photography in a humorous, inane way. And his works certainly recall the « gags and jokes » of early staged photography. In addition, the use of titles by Nauman also bears resemblance to Lizene’s. Compare, for example, Nauman’s Playing A Note on the Violin While I Walk Around the Studio, a video from 1967-1968, with Lizene’s Minor Master from Liege Entering the Frame of a Photo: in both cases a « banal » action, seen in the image, is tautologically explained in the title. However, Lizene’s approaches are even more enlarged than in the case of Nauman, since the banality and foolishness of Lizene’s scenes is reduced to new levels. Compared to the Conceptual canon, Lizene much more explicitly uses actions in order to put himself into perspective, thereby rendering his work with a distinctly absurd, humoristic undertone. As a matter of fact, Lizene remarked « [that] on August 28, 1990, he realized he was one of the inventors of the ‘comic Conceptualism’ of the early 1970s. » (Lizene, 1990: 43)

Other « inventors of comic Conceptualism » might be the American artist William Wegman and the Dutch artists Bas Jan Ader and Ger Van Elk, whose performative works from the early 1970s are sometimes very similar to Lizene’s . For example, Wegman’s Reading Two Books (1971)-in which the artist is cross-eyed, as it were, in order to read two books at the same time-recalls Lizene’s recordings of absurd activities such as « putting his nose against the surface of the photograph. » Van Elk’s photo works in which he represents the word « OK » -such as the Co-Founder of the Word O.K – Marken (No. 5) (1971)-are related to Lizene’s visual plays with the picture frame. (fig. Il. l 0) To conclude, Ader’s photographs of his « falls »-such as Broken Fall (Geometric), Westkapelle, Holland (1971), by means of which he challenges the ideal of the heroic master-aligns with Lizene’s self-mocking attitude. (Goldstein & Rorimer, 1995: 46-47)

Just like Bruce Nauman, around 1970 Wegman, Ader, and Van Elk were all working in and around Los Angeles. Therefore, their work was recently categorized as California Conceptualism, with the use of the body as a material as one of its defining characteristics. (Lewallen, 2012: 78) However, the resemblance between Lizene’s work and that of Wegman, Ader, or Van Elk is rather based on coincidence, since Lizene states he never met one of these artists nor knew their work at that time. (J. Lizene, Interview, Liege, July 14, 2014) More direct artistic links are likely to be found in Brussels Surrealism on the one hand, and the Fluxus movement on the other.

Due to the absurd, humoristic character, some of Lizene’s strategies are perfectly in line with, for example, those of Paul Nouge in his Subversion of Images [Subversion des Images] (1929-30) or Rene Magritte in his amateur snapshots, some of which served as models for his paintings. As a matter of fact, the strategy of staging, of constructing an image in a theatrical, well-reasoned way, is one of the key concepts of Nouge and the Brussels Surrealists. Nouge’s photo series Subversion of Images consists of nineteen precisely composed still lifes and tableaux vivants, in which some of Nouge’s Surrealist comrades appear as performers in an absurd act. The work remained « hidden » until 1968, the year after Nouge’s death, when Marcel Marien collected and published the images in Les Levres nues under the generic title Subversion of Images. (Meuris, 1993: 297; De Naeyer, 1995: 9; Canonne, 2007: 27) In fact, this photo series is a visualization of Nouge’s theory of the « disturbing object » (objet bouleversant), which he developed in connection with the paintings of Rene Magritte. (Nouge, 1956: 239-241) According to Nouge, one of the strategies that rendered the subversive quality of Magritte’s works was the deliberate decontextualization or isolation of daily objects. After isolating the object, it could be transformed by a modification of the object itself, a change of scale of the object, or a change of decor. (Nouge, 1956: 240)

Connected with the visual strategies that are linked with the theory of the « disturbing object » and demonstrated in Subversion of Im ages, is the method of staging. Contrary to the idea of « automatic writing » (ecriture automatique) propagated by the French Surrealists, the Brussels Surrealists supported the idea of the well-reasoned, constructed image. Concerning the creation of photographic images, they would rather stage the images, including (themselves as) actors and « disturbing objects, » than hunt for « found objects » (objets trouves) in the streets. (De Naeyer, 1995: 21) When the Minor Master from Liege created his staged photo series in 1971, Nouge’s Subversion of Images had only been published three years earlier. However, Lizene claims he did not know Nouge’s work at that time. Nevertheless, he does acknowledge his interest in Magritte and his « manipulation of the image » (J. Lizene, Interview, Liege, July 14, 2014).

Also within Fluxus the staging of events was a key activity. Dedicated to the dissolution of the dichotomy between art and life, Fluxus performances often included very banal actions taken from daily life experience. They were characterized by simplicity, playfulness, the acceptance of chance, specificity, presence in time (ephemerality), and musicality (the idea that a work is conceived as a score, which can be executed by an artist other than the creator)-all of these being core concepts of Fluxus. (Friedman, 1989/1998: 247-251) Lizene’s « performed photo works »-Minor Master from Liege Having Attached His Tie to the Photo Frame, Minor Master from Liege Entering the Frame of a Photo; etc.-actually match most of these characteristics. What differs, however, is Lizene’s use of photography to capture the event in a very specific moment, which totally determines the content of the work and responds to the medium specificity of photography, which is, for example, defined by a frame.

The Fluxus artist with whom Lizene shows most affinity is undoubtedly Ben Vautier, who, residing in Nice, was appointed by George Maciunas as the director of »Fluxus South. » (Smith, 1998: 11) The Fluxus art movement, noted for the blending of different artistic disciplines and the use of unconventional media, was founded in Germany in 1962 by American artist George Maciunas, and its members included Joseph Beuys, John Cage, Yves Klein, and Ben Vautier. Lizene shows some affinities with this last member, especially. Not only do he and Ben share an admiration for Dadaïsm, Duchamp, and Cage; both their works are also permeated with irony and self-mockery. In the case of Ben, this is expressed in a constant alternation of claiming to be the world’s greatest genius and undermining his own claims. « I want to be the greatest in not being great, » and « I want to neutralize my ego in order to affirm my ego, » as he stated in an interview with Ermeline Lebeer in 1973. [my translations] (Lebeer 1997: 145) His well-known text-based paintings include inscriptions like, for example, « Art is useless/go home » [Lart est inutile/rentrez chez vous] or « I discovered something new in art, but I will not tell you about it; it is a secret. » Ben and Lizene actually met in 1971 through gallery owner Daniel Templon in Paris but had already been corresponding with each other since 1969. In that year, Guy Jungblut had sent Ben an invitation to Lizene’s exhibition at gallery Yellow Now on which a quotation after Marcel Duchmap was written: « We have to abolish the idea of judgment. » [my translation] Ben had responded to this by adding « I don’t walk to that which makes the others run, » marking the beginning of an exchange of letters between the artists. [my translation] (Gielen, 2003: 42) (…)

[sociallinkz]