[sociallinkz]

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Köln, museum Ludwig, exhibition “Suchan Kinoshita, In ten Minuten”

« Isofollies » (2007) de Suchan Kinoshita est une installation constituée de quatorze étranges météorites, des astéroïdes à la composition inconnue. Masses ventrues, volumes divers et singuliers, ces mégalithes agissent comme de monumentales scories : ce sont des ballots pétrifiés. Une première série de ces sculptures est apparue en 2006. Sur le lieu même de son exposition, dans les caves et greniers de la galerie qui l’accueille pour l’occasion, l’artiste a rassemblé, sérié, entassé des objets de rebut, des déchets de toutes sortes, ce qui au fil du temps a été abandonné, ce qui a perdu son utilité. Elle en a constitué des ballots de tailles diverses, elle a momifié au sens propre comme au sens figuré ces rebuts, les serrant dans de longues bandes de plastique industriel, élastique et noir, roulant ces balles sur le sol, les compressant, compactant ces déchets ainsi fossilisés. C’est le temps du lieu, son histoire, que voici pétrifié. Onze aérolithes constituent l’œuvre, distribués dans l’espace d’exposition comme une constellation3. En 2007, lors d’une exposition personnelle à l’Ikon Gallery à Birmingham sont apparus trois nouveaux aérolithes que l’artiste nomme désormais « Isofollies », du nom du plastique qu’elle utilise. Ce sont, cette fois, les résidus du montage de sa propre exposition qu’elle utilise. Le premier ensemble de ces sculptures devient ainsi un principe délocalisé.

Suchan Kinoshita est invitée en avril 2007, par la 8e biennale de Sharjah aux Emirats Arabes Unis. Avec son consumérisme effréné, ses îles artificielles, ses tours de luxe audacieuses, ses usines de désalinisation à énergie réduite et ses banlieues taillées dans les sables du désert, les Emirats Arabes unis sont le cauchemar des défenseurs de l’environnement. C’est cette problématique que les commissaires de la biennale ont décidé d’aborder : «Still Life, art, ecology and the political of change» est menée dans un urgent processus d’enquête et veut mettre l’accent sur le rôle renouvelé de l’art dans la résolution d’un large éventail de questions qui affectent directement, de façon alarmante, la vie telle que nous la connaissons. Il s’agit d’aborder les défis sociaux, politiques et environnementaux qui se posent face au développement humain excessif et l’épuisement progressif des réserves naturelles. Tout naturellement, Suchan Kinoshita propose de produire un troisième ensemble d’ « Isofollies ». Cette nouvelle constellation est bien évidemment produite in situ, avec les déchets et rebuts trouvés sur place. Né dans un dans un contexte domestique, temps compressé d’un lieu, recyclage du vécu de ses habitants successifs, le principe même de l’œuvre prend à Sharjah une signification augmentée et en quelque sorte planétaire.

Ces constellations successives agissent bien comme un espace de pensée à géométrie variable, du singulier au plus universel : Suchan Kinoshita a enfoui les rebuts d’une maisonnée, ensuite les résidus d’une production d’exposition, enfin un extrait condensé des déchets d’une mégalopole. Dans une quatrième déclinaison de l’œuvre, en 2014, elle a aussi enfoui les objets et souvenirs personnels d’une personne disparue, traces mémorielles qui acquièrent ainsi une nouvelle vivacité, abstraite et universelle. Rien n’est jamais figé dans l’œuvre de Suchan Kinoshita. Son travail protéiforme se développe sans cesse et se transforme avec les expériences accumulées. L’artiste considère chaque exposition comme le fragment d’un tout dont elle ne contrôle ni les limites, ni l’aboutissement. Bien que reliées entre elles par la volonté de l’artiste, les pièces dont elle est l’auteur s’enrichissent de connotations imprévues et peuvent se comprendre différemment selon les contextes spécifiques. Intéressant à cet égard est de considérer les divers moments et lieux où la constellation conçue à Sharjah est réapparue. Dans cette exposition dévolue à la « carrière du spectateur » (2009), certainement un job à temps plein, les quatorze éléments d’ « Isofollies », sont posés en contrepoint d’un monumental rideau de velours vert sur lequel, en poursuite, s’inscrit le halo lumineux d’un projecteur et derrière lequel tourne lentement sur elle-même une sphère à miroirs. Dans un rapport entre le tellurique et l’aérien, l’installation évoque une conjonction d’éléments qui renvoie à l’univers de René Magritte et ses mystères. Disposée en 2009 sous les voûtes du Pavillon de l’Horloge qui donne accès à la Cour Carrée du Louvre à Paris, « Isofollies » opère comme un chaos minéral face à l’ordonnancement classique des colonnes à cannelures érigées par l’architecte Jacques Lemercier au 17e siècle. Lors de son exposition « In ten minuten » (le temps est un paramètre essentiel dans l’oeuvre de Kinoshita) au Musée Ludwig à Cologne (2010) elles font face à cette autre œuvre que l’artiste nomme « Engawa », ponton en méranti, aux fines lattes de parquet ponctuées de lignes colorées et de petits carreaux jaunes, bleus et rouges, rythmé par une série de pilotis. L’engawa, dans l’architecture traditionnelle japonaise, est une passerelle de bois extérieure, un plancher surélevé, courant le long de la maison. C’est un lieu de passage, coiffé d’un toit pentu ; l’engawa module la relation entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur. On s’y arrête, on s’y assoit afin de contempler le jardin ou le paysage, on y médite. Ici, face à ce champ d’aérolithes qui rappelle l’épure totale du jardin japonais. Le « Sakuteiki », livre de conception du jardin, s’ouvre sur le titre de « L’art de disposer les pierres ». En 2011, lors de son exposition « The Right Moment at the Wrong place », au Museum De Paviljoens à Almere, elle concentre « Isofollies », dans un étroit et sombre réduit, retour à un obscur chaos des origines. Enfin, lors de l’exposition « Tussenbeelden » organisée à Schunck* (Heerlen 2014), le commissaire Paul Van der Eerden les compare aux « Bolis » de la culture Bambara, ces reliquaires manifestation de la force vitale dont la fonction principale est d’accumuler et de contrôler la force de vie naturelle. Ils contiennent des éléments divers, leur surface est sans cesse imprégnée de couches de libations. Pour l’initié, le « Boli » a une présence qui transcende l’objet lui-même ; objet réel dans un espace réel, il occupe aussi un espace mental dans la mémoire de la communauté.

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Köln, museum Ludwig, exhibition “Suchan Kinoshita, In ten Minuten”

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Liège (B), galerie Nadja Vilenne

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Paris, Cour Carrée du Louvre.

Suchan Kinoshita’s Isofollies (2007) is an installation composed of fourteen strange meteorites or asteroids, their composition unknown. Bulbous masses, varied and singular volumes, these megaliths act like monumental scoria: they are petrified bundles. A first series of these sculptures appeared in 2006. In the exhibition space itself, in the basement and the attic of the gallery where she was showing, the artist gathered, serialized, and bundled up all manner of objects – waste, in fact, those things that over time had been abandoned, had stopped being useful. With these, she composed bundles of varying sizes; she mummified the scrap, literally and figuratively, by packing it using long strips of industrial plastic, elastic and black, and then rolling the resulting bundles on the floor, compressing them and thus compacting the fossilized waste. What is petrified here is the time of the place, its history. The eleven aeroliths that compose the work were distributed in the exhibition space like a constellation. In 2007, during a solo show at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, three new aeroliths appeared, and from that moment on the work took on the name Isofollies, after the plastic wrap used to make it. At the Ikon Gallery, she used the residues from the installation process of her show. The first ensemble of these sculptures thus became a delocalized principle.

Suchan Kinoshita was invited to the 8th Sharjah Biennial, in the United Arab Emirates, in April 2007. With its unbridled consumerism, its artificial islands, its ostentatious luxury towers, its ‘green’ desalination plants and its suburbs carved onto the desert sands, the United Arab Emirates are a nightmare for environmentalists. And that was precisely the problem that the artistic directors of the Biennial decided to address: Still Life, Art, Ecology and Political Change is inscribed in an urgent and ongoing research process whose goal is to highlight the renewed role that art can play in the resolution of a large panoply of questions that have a direct, and alarming, effect on life as we know it. It was about addressing the social, political and environmental challenges raised by excessive development and the ever-increasing depletion of natural resources. Naturally, against this background, Suchan Kinoshita decided to the produce a third set of her Isofollies. This new constellation was, like the other ones, produced in-situ, with waste and scraps found on the spot. Born in a domestic context, the compressed time of a place, a recycling of the lived experience of its successive inhabitants, at the Sharjah Biennial the very principle of the work took on a heightened, and in some ways planetary, meaning.

These successive constellations act like a space of thought with a variable geometry, from the singular to the more universal: Suchan Kinoshita buried the waste of a household, then the residues produced by the mounting of an exhibition, and lastly the condensed extracts of the waste of a megalopolis. In a fourth version of the work, from 2014, she buried the personal objects and souvenirs of a person who had died, traces of memories that in her work found a new vitality, at once abstract and universal. Nothing in Suchan Kinoshita’s work is ever fixed. Her shift-shaping work is always in progress, always being transformed in light of accumulated experiences. The artist always treats every exhibition like a fragment of a whole whose limits, and ends, are outside of her control. The works are linked by the will of the artist, but they are also enriched by unforeseen connotations and can be read differently depending on their context. It is interesting, in this regard, to consider the various moments and places where the constellation conceived for the Sharjah Biennial has reappeared. In this exhibition devoted to the ‘career of the spectator’ (2009), certainly a full-time job, the fourteen elements of the Isofollies were placed in counterpoint to a monumental green velvet curtain upon which a spotlight projected the luminous halo of a projector and behind which a disco ball turned slowly on its axis. In this relation between the telluric and the aerial, the installation evokes a conjunction of elements that refer to the universe of René Magritte and his mysteries. Placed under the archways of the Pavillon de l’Horloge, the eastern entrance to the Cour Carrée of the Louvre in Paris, the Isofollies operated like a mineral chaos amidst the classical layout of the fluting columns erected by the architect Jacques Lemercier in the seventeenth century. For her exhibition In Ten Minuten (time is an essential parameter of this artist’s work), at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne (2010), she placed the Isofollies in relation to another work, Engawa, a pontoon made of meranti wood cut into thin parquet slats, and dotted here and there by coloured lines and small yellow, blue and red squares, and punctuated by the stilts that support the structure, but that overshoot it in places. In traditional Japanese architecture, the engawa is a raised wooden walkway that surrounds the house, almost like a porch. It’s a passageway, covered by a slanted roof. The engawa mediates the relation between inside and outside. It’s a place to stand, to sit down and contemplate the garden or landscape, to meditate. In this case, a place to face the field of aeroliths so reminiscent of the total sparseness of the Japanese garden. The Sakuteiki, the oldest Japanese book about gardening, opens with the title ‘The Art of Setting Stones’. In 2011, for her show The Right Moment at the Wrong Place, at the Museum De Paviljoens, in Almere, the Netherlands, she concentrated the Isofollies into a narrow and dark enclave, a return to the obscure chaos of its origins. Finally, during the exhibition Tussenbeelden at the Schunck* (Heerlen, 2014), curator Paul Van der Eerden compared the Isofollies to the Bolis – reliquary manifestations of the vital force whose primary function is to accumulate and control the force of natural life of the Bambara people in West Africa. The Bolis contain a variety of elements, their surface is constantly impregnated by layers and layers of libations. For the initiated, the Boli is a presence that transcends the object itself; a real object in a real space, it occupies also a mental space in the memory of the community.

[sociallinkz]

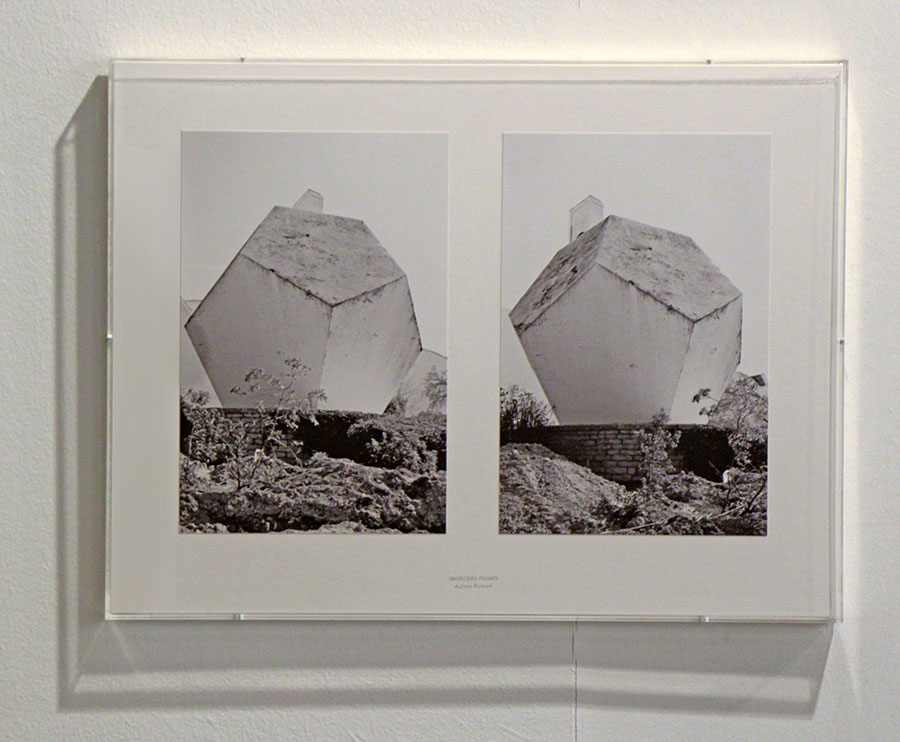

Aglaia Konrad

Undecided frames, 2016 (Carrara, 2010)

colors photography, 41 x 54 cm. Ed 3/3 + 2 ep.a.

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Köln, museum Ludwig, exhibition “Suchan Kinoshita, In ten Minuten”

For its tenth participation at Arco Madrid, the Nadja Vilenne Gallery has chosen to present the work of two artists, Suchan Kinoshita and Aglaia Konrad. The dialogue between these two artists over the years has yielded a singular resonance between their works.

1.

For more than twenty years, Aglaia Konrad has tirelessly observed, investigated and translated the city and it urbanity, this global metropolis, be it Beijing or São Paulo, Cairo, Dakar or Chicago. She analyses the sociological field, the socio-political parameters; she focuses her attention on the generic modernity and genealogy of concrete architectures. Her work, inscribed in the very heart of the metropolis, senses and teases out its drives. And, sometimes, it also distances itself from that core, the better to understand its knots of its circulation, its expansion, the access into it, its relation to the landscape. Over the course of her travels, Aglaia Konrad has amassed a vast body of images that answer to the standards of the documentary. And that body is an indexed trace of the real constituted out of an infinity of reproducible images. That said, none of the images in it has a specific support, a fixed surface, at the outset, none claims for itself, a priori, any canon of the photographic art as usually codified. The mobilized image could become a traditional black-and-white photograph, a simple inkjet scan, a digital photocopy, part of a slide projection, a colour negative print, or be enlarged to the size of the exhibition space. Or it could be the object of books and other publications. It all depends. Each of the images Aglaia Konrad archives stems from a double perspective: all are a recording of the real, and all will reveal their subjective and critical potential once they have been activated. Their discursive power just as much as their scenography are what establish the very bases for the relation between the image and the viewer.

The series Undecided Frames was born – paradoxically – precisely at a moment when she had to decide a specific and contextual use for the images. Immersed in her subject, Aglaia Konrad takes multiple shots, and some are nearly identical – they are so similar, and yet so singular, that the artist remains undecided as to which one to choose from the archive. Hence the – courageous – idea not to choose between two similar shots, an idea that, ipso facto, becomes a decision to confront the two shots, to juxtapose them in the same frame, in which the two photographs are separated by a thin passé-partout. The new image thus composed is called Undecided Frame.

From Mexico to Créteil, from Tokyo to Chicago, from Carrara to the Grande Dixence Dam, we slip quite naturally into playing the game of spotting the differences, of noticing, in the images placed side by side, a shift in the angle, a difference in the depth of field, the disappearance, or appearance, of certain details. ‘In Time, the same object is not the same after a one-second interval’, says Duchamp. In Note no. 7, Duchamp evokes the difference between ‘semblance/similarity’, and a bit further on he adds: ‘there is a crude conception of the déjà vu that leads from a generic grouping (two trees, two boats) to the most identical “castings.” It would be better to try to go into the infra-thin interval that separates two “identicals” than to conveniently accept the verbal generalization that makes two twins look like two drops of water’.1 What Duchamp is discussing in this passage is his work on the infra-thin, and Aglaia Konrad’s Undecided Frames bear a singularly close kinship to that. With her non-choice, she opens the perceptive field while our gaze follows the displacement of the lens, however ‘thin’ it might be. The point here isn’t to come as close as possible to the threshold of the perceptible, or of the singularization between two images, but to open up an expanded field. ‘With each fraction of duration’, Thierry Davila observes, speaking of Duchamp’s infra-thin, ‘all future and past fractions are reproduced. All these past and future fractions coexist in a present that is already no longer what we ordinarily call the present instant, but a sort of present with multiple extensions. It is in these multiple extensions of time that the subject addressed here circulates, it is in their incessant activation that it finds the means for a renewed plasticity’.2 Indeed, from one image to the other, in the case of Aglaia Konrad’s photographs, we find ourselves not only facing the same object or subject, though our perception of it is different, we also find ourselves confronted by different objects or subjects, if nothing else because of the time interval that exists between the two shots. This renewed, increased even, plasticity resides in the infra-thin that separates the two shots placed side by side. We are not in fact looking at two juxtaposed photographs but at one image, composed of two shots. And this dialectic of semblance and difference sharpens our perception of the real. The repetition of this same deferred action becomes an imbricated repetition. The reprise, by the infinitesimal difference at the heart of the logic of the same, impacts our perception of the real.

2.

Suchan Kinoshita’s Isofollies (2007) is an installation composed of fourteen strange meteorites or asteroids, their composition unknown. Bulbous masses, varied and singular volumes, these megaliths act like monumental scoria: they are petrified bundles. A first series of these sculptures appeared in 2006. In the exhibition space itself, in the basement and the attic of the gallery where she was showing, the artist gathered, serialized, and bundled up all manner of objects – waste, in fact, those things that over time had been abandoned, had stopped being useful. With these, she composed bundles of varying sizes; she mummified the scrap, literally and figuratively, by packing it using long strips of industrial plastic, elastic and black, and then rolling the resulting bundles on the floor, compressing them and thus compacting the fossilized waste. What is petrified here is the time of the place, its history. The eleven aeroliths that compose the work were distributed in the exhibition space like a constellation.3 In 2007, during a solo show at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, three new aeroliths appeared, and from that moment on the work took on the name Isofollies, after the plastic wrap used to make it. At the Ikon Gallery, she used the residues from the installation process of her show. The first ensemble of these sculptures thus became a delocalized principle.

Suchan Kinoshita was invited to the 8th Sharjah Biennial, in the United Arab Emirates, in April 2007. With its unbridled consumerism, its artificial islands, its ostentatious luxury towers, its ‘green’ desalination plants and its suburbs carved onto the desert sands, the United Arab Emirates are a nightmare for environmentalists. And that was precisely the problem that the artistic directors of the Biennial decided to address: Still Life, Art, Ecology and Political Change is inscribed in an urgent and ongoing research process whose goal is to highlight the renewed role that art can play in the resolution of a large panoply of questions that have a direct, and alarming, effect on life as we know it. It was about addressing the social, political and environmental challenges raised by excessive development and the ever-increasing depletion of natural resources. Naturally, against this background, Suchan Kinoshita decided to the produce a third set of her Isofollies. This new constellation was, like the other ones, produced in-situ, with waste and scraps found on the spot. Born in a domestic context, the compressed time of a place, a recycling of the lived experience of its successive inhabitants, at the Sharjah Biennial the very principle of the work took on a heightened, and in some ways planetary, meaning.

These successive constellations act like a space of thought with a variable geometry, from the singular to the more universal: Suchan Kinoshita buried the waste of a household, then the residues produced by the mounting of an exhibition, and lastly the condensed extracts of the waste of a megalopolis. In a fourth version of the work, from 2014, she buried the personal objects and souvenirs of a person who had died, traces of memories that in her work found a new vitality, at once abstract and universal. Nothing in Suchan Kinoshita’s work is ever fixed. Her shift-shaping work is always in progress, always being transformed in light of accumulated experiences. The artist always treats every exhibition like a fragment of a whole whose limits, and ends, are outside of her control. The works are linked by the will of the artist, but they are also enriched by unforeseen connotations and can be read differently depending on their context. It is interesting, in this regard, to consider the various moments and places where the constellation conceived for the Sharjah Biennial has reappeared. In this exhibition devoted to the ‘career of the spectator’ (2009), certainly a full-time job, the fourteen elements of the Isofollies were placed in counterpoint to a monumental green velvet curtain upon which a spotlight projected the luminous halo of a projector and behind which a disco ball turned slowly on its axis. In this relation between the telluric and the aerial, the installation evokes a conjunction of elements that refer to the universe of René Magritte and his mysteries. Placed under the archways of the Pavillon de l’Horloge, the eastern entrance to the Cour Carrée of the Louvre in Paris, the Isofollies operated like a mineral chaos amidst the classical layout of the fluting columns erected by the architect Jacques Lemercier in the seventeenth century. For her exhibition In Ten Minuten (time is an essential parameter of this artist’s work), at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne (2010), she placed the Isofollies in relation to another work, Engawa, a pontoon made of meranti wood cut into thin parquet slats, and dotted here and there by coloured lines and small yellow, blue and red squares, and punctuated by the stilts that both support the structure and overshoot it in places. In traditional Japanese architecture, the engawa is a raised wooden walkway that surrounds the house, almost like a porch. It’s a passageway, covered by a slanted roof. The engawa mediates the relation between inside and outside. It’s a place to stand, to sit down and contemplate the garden or landscape, to meditate. In this case, a place to face the field of aeroliths so reminiscent of the total sparseness of the Japanese garden. The Sakuteiki, the oldest Japanese book about gardening, opens with the title ‘The Art of Setting Stones’. In 2011, for her show The Right Moment at the Wrong Place, at the Museum De Paviljoens, in Almere, the Netherlands, she concentrated the Isofollies into a narrow and dark enclave, a return to the obscure chaos of its origins. Finally, during the exhibition Tussenbeelden at the Schunck* (Heerlen, 2014), curator Paul Van der Eerden compared the Isofollies to the Bolis – reliquary manifestations of the vital force whose primary function is to accumulate and control the force of natural life of the Bambara people in West Africa. The Bolis contain a variety of elements, their surface is constantly impregnated by layers and layers of libations. For the initiated, the Boli is a presence that transcends the object itself; a real object in a real space, it occupies also a mental space in the memory of the community.

3.

This time, the Sharjah Isofollies are made to resonate with the work of Aglaia Konrad. And the dialogue between the work of these two artists goes well beyond the fact that Suchan Kinoshita’s Isofollies are composed of the waste produced by a megalopolis, and the fact that the megalopolis is one of the main subjects of observation and reflection of and in Aglaia Konrad’s work. In 2007, Aglaia Konrad inaugurated a vast cycle of works – Shaping Stones and Concrete & Samples – that focus on architectures with sculptural forms. In Sculpture House, Konrad turned her attention to the first Belgian house built in shotcrete (by the architect Jacques Gillet, between 1967 and 1968). The work is the result of her research and exploration of the synthesis between the functional and aesthetic dimensions of the house’s architecture: it is composed of concrete sails that offer a multiplicity of points of view that could not have been captured with a single shot. That being so, the artist reveals to us this veritable sculpture through slow travelling shots in which the concrete appears as an organic force, and the house as perfectly integrated into the surrounding nature and foliage, with the interior extending outwards and vice versa. Konrad subsequently filmed the Church of the Holy Trinity, the expressionist masterpiece of Austrian artist Fritz Wotruba (1907-1975), in all of its brutalist power. Guided by his tectonic approach to stone sculpture, Wotruba’s monumental construction in Vienna piles and dovetails gigantic concrete blocks. Aglaia Konrad’s camera becomes the best witness of a spiritual architecture, unified in its chaos, whose primitive and atemporal image is reminiscent of the sacred megaliths at Stonehenge. With Concrete & Samples II: Blockhaus, she did the same with the Church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay, in Nevers. Conceived by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, this monolithic, enigmatic structure appears like a bunker in béton brut. These studies eventually lead Aglaia Konrad to the quarries of Carrara, where she photographed and filmed the mineral landscape, the marble mountains, a landscape, constantly in transformation, that seems to have been sculpted, something like a hollow sculpture out of which have been extracted, over time, the innumerable masterpieces that punctuate the history of architecture and sculpture. In her more recent work, Konrad has created a lapidarium of construction debris; and she has, at the same time, indexed the upright stones of the Neolithic cromlech at Avebury in prints on baryta paper. Monoliths, megaliths, the tectonic force of béton brut, organic or brutalist architecture, stone and sculpture – all of this confronts us with the relation between nature and culture, the mineral kingdom and the dynamism of the living, the chaos of origins and the construction of the world. ‘Before the earth and the sea and the all-encompassing heaven / came into being, the whole of nature displayed but a single / face, which men have called Chaos; a crude unstructured mass / nothing but weight without motion, a general conglomeration / of matter composed of disparate, incompatible elements’.4 So writes Ovid in his Metamorphoses. Suchan Kinhoshita’s Isofollies evoke the same things: the chaos of origins, the power of the mineral, a petrifying inertia, the dynamism of the living, the megalith and the sculpture, recycling and metamorphosis, cosmogony, the constellation and the song of the universe, primordial forces and the excessive overabundance – unbridled and disquieting – of the world today, the world that she recycles and reorganizes like one of the Titanides or, better yet, like Sisyphus himself.

4.

In this new part of the Undecided Frames series, we should note the aerial views, of the Gobi Desert or Siberia, that attest to human organization; the metal weatherboardings that seem to struggle to constrain this tower in Mexico, before which the passing carts of green plants seem all the more flimsy; the urban views of Tokyo, Chicago or Hong Kong, their images so similar and yet so different; the mighty force of the Grande Dixence Dam, in the Valais, whose interior architecture seems to rival the stacking and dovetailing of monoliths in Fritz Wotruba’s church in Vienna. The movement of the lens before the dam gives this thing that harbors all the forces of nature an even greater dynamism. We should note as well the stained glass doors and mirrors photographed in Porto. In all of these, Aglaia Konrad seems to be searching out the thresholds of the singularities that differentiate two quasi-identical shots. There is the lapidarium of the archeological museum in Cologne, there is of course Carrara, nor should we forget the brutalist cylindrical towers, built by Gérard Grandval, known as the Choux de Créteil, or Créteil Cabbage. The very name of these concrete towers, we note in concluding, refers us to nature.

Jean Michel Botquin

1 Marcel Duchamp, Duchamp du Signe, suivi de Notes, eds. Michel Sanouillet and Paul Matisse (Paris: Flammarion, 2008), p. 290.

2 Thierry Davila, De l’Inframince. Brève histoire de l’imperceptible de Marcel Duchamp à nos jours (Paris: Editions du Regard, 2010)

3 Suchan Kinoshita, yukkurikosso yoi, at Nadja Vilenne Gallery, Liège, 2006. Collection Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht.

4 Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Davide Raeburn (London: Penguin Books, 2004), I. 4-9.

[sociallinkz]

Aglaia Konrad

Undecided frames, 2016 (Grande Dixence 2012) colors photography, 41 x 54 cm. Ed 3/3 + 2 ex.a

Suchan Kinoshita

Isofollies, 2007-2017

Mixed media (wrape, plastic, oil), variable dimensions

Installation in Köln, museum Ludwig, exhibition “Suchan Kinoshita, In ten Minuten”

Pour sa dixième participation à Arco Madrid, la galerie Nadja Vilenne a choisi de proposer les œuvres de deux artistes, Suchan Kinoshita et Aglaia Konrad. Du dialogue qui s’est instauré entre les deux artistes est né une singulière résonance entre les œuvres.

1.

Inlassablement depuis plus de vingt ans, Aglaia Konrad observe, investit, traduit la ville et son urbanité, cette métropole globale, qu’il s’agisse de Pékin ou de Sao Paulo, du Caire, de Dakar ou de Chicago. Elle en analyse le champ sociologique, les paramètres sociopolitiques, focalise son attention sur les architectures de béton, leur modernité générique et leur généalogie. Son travail s’inscrit au cœur même de la métropole dont elle perçoit les pulsions, s’en échappant parfois pour mieux comprendre les nœuds de circulation, l’expansion, les accès, la relation au paysage. Au fil de ses voyages, Aglaia Konrad constitue un vaste corpus d’images qui répond aux standards du documentaire. C’est une trace indexée du réel constituée d’une infinité d’images reproductibles. Pourtant, aucune n’a d’emblée un support précis, une surface fixe, aucune ne se revendique a priori d’un quelconque canon de l’acte photographique tel qu’habituellement codifié. L’image mise en œuvre pourra être argentique ou simple scan à jet d’encre, photocopie numérique ou projection de diapositives, épreuve négative ou impression marouflée à l’échelle de l’espace d’exposition, comme elle pourra faire l’objet de livres et de cahiers. Ce sera selon. Chacune de ces images qu’archive Aglaia Konrad procède de cette double perspective : toutes sont l’enregistrement du réel et toutes révèleront leur potentiel subjectif et critique dès lors qu’elles seront mises en œuvre. Tant leur pouvoir discursif que leur scénographie établiront les bases mêmes d’une possible relation entre l’image et celui qui la regarde.

C’est justement au moment de décider d’une utilisation ponctuelle et contextuelle qu’est – paradoxalement – née la série des « Undecided Frames ». Immergée dans son sujet, Aglaia Konrad multiplie les prises de vue. Certains clichés sont parfois fort proches, tellement semblables et chacun si singulier, que l’artiste reste dans l’indécision quant à celui qu’il faut prélever dans l’archive. D’où l’idée d’assumer – courageusement – le choix de ne pas choisir entre deux clichés similaires, ce qui entrainera, ipso facto, une décision : celle de confronter les deux clichés, de les juxtaposer sous un même encadrement, les deux photographies séparées par un mince passe-partout, et de nommer cette nouvelle image ainsi constituée « Undecided Frame ».

De Mexico à Créteil, De Tokyo à Chicago, de Carrare au barrage de la Grande Dixence, on se prend bien naturellement à jouer aux jeux des différences, constatant entre les images placées côte à côte un déplacement de l’objectif, une profondeur de champ distincte, la disparition ou l’apparition de quelques détails. « Dans le temps, un même objet n’est pas le même à une seconde d’intervalle »1. La citation est de Marcel Duchamp. Dans sa note n°7, Duchamp évoque « la semblablité/la similarité »; plus loin dans ses remarques, il ajoute qu’ « il existe une conception grossière du déjà vu qui mène du groupement générique (deux arbres, deux bateaux), aux plus identiques « emboutis ». Il vaudrait mieux chercher à passer dans l’intervalle infra mince qui sépare deux identiques qu’accepter commodément la généralisation verbale qui fait ressembler deux jumelles à deux gouttes d’eau ». Duchamp évoque là ses travaux sur l’infra mince et les « Undecided Frames » d’Aglaia Konrad s’en approchent singulièrement. Par le non choix qu’elle opère, l’artiste ouvre le champ perceptif tandis que notre regard suit le déplacement de l’objectif, si mince celui-ci soit-il. Il ne s’agit pas ici de toucher au plus près les seuils de perceptibilité ou de singularisation entre deux clichés, mais bien d’ouvrir un champ étendu. « A chaque fraction de la durée, note Thierry Davila, à propos de l’infra-mince duchampien, se reproduisent toutes les fractions futures et antérieures. Toutes ces fractions passées et futures coexistent dans un présent qui n’est déjà plus ce que l’on appelle ordinairement l’instant présent, mais une sorte de présent a étendue multiple. C’est dans ces multiples étendues du temps que le sujet ici aborde circule, c’est dans leur incessante activation qu’il trouve les moyens d’une plasticité renouvelée ».2 De fait d’un cliché à l’autre, dans le cas des photographies d’Aglaia Konrad, nous sommes face au même objet ou sujet, nous en avons une perception différente, et nous sommes aussi face à des objets ou sujets différents, ne fut-ce qu’en raison de l’intervalle de temps qui existe entre deux prises de vue. Cette plasticité renouvelée, augmentée même, réside dans l’infra mince qui sépare les deux prises de vue mise côte à côte. Nous ne sommes même plus devant deux photographies juxtaposées mais bien devant une image composée de deux clichés. Et cette dialectique du semblable et de la différence aiguise notre perception du réel. La répétition de cette même action différée devient une répétition imbriquée. La reprise, par la différence même infime au sein de la logique du même impacte notre perception du réel.

2.

« Isofollies » (2007) de Suchan Kinoshita est une installation constituée de quatorze étranges météorites, des astéroïdes à la composition inconnue. Masses ventrues, volumes divers et singuliers, ces mégalithes agissent comme de monumentales scories : ce sont des ballots pétrifiés. Une première série de ces sculptures est apparue en 2006. Sur le lieu même de son exposition, dans les caves et greniers de la galerie qui l’accueille pour l’occasion, l’artiste a rassemblé, sérié, entassé des objets de rebut, des déchets de toutes sortes, ce qui au fil du temps a été abandonné, ce qui a perdu son utilité. Elle en a constitué des ballots de tailles diverses, elle a momifié au sens propre comme au sens figuré ces rebuts, les serrant dans de longues bandes de plastique industriel, élastique et noir, roulant ces balles sur le sol, les compressant, compactant ces déchets ainsi fossilisés. C’est le temps du lieu, son histoire, que voici pétrifié. Onze aérolithes constituent l’œuvre, distribués dans l’espace d’exposition comme une constellation3. En 2007, lors d’une exposition personnelle à l’Ikon Gallery à Birmingham sont apparus trois nouveaux aérolithes que l’artiste nomme désormais « Isofollies », du nom du plastique qu’elle utilise. Ce sont, cette fois, les résidus du montage de sa propre exposition qu’elle utilise. Le premier ensemble de ces sculptures devient ainsi un principe délocalisé.

Suchan Kinoshita est invitée en avril 2007, par la 8e biennale de Sharjah aux Emirats Arabes Unis. Avec son consumérisme effréné, ses îles artificielles, ses tours de luxe audacieuses, ses usines de désalinisation à énergie réduite et ses banlieues taillées dans les sables du désert, les Emirats Arabes unis sont le cauchemar des défenseurs de l’environnement. C’est cette problématique que les commissaires de la biennale ont décidé d’aborder : «Still Life, art, ecology and the political of change» est menée dans un urgent processus d’enquête et veut mettre l’accent sur le rôle renouvelé de l’art dans la résolution d’un large éventail de questions qui affectent directement, de façon alarmante, la vie telle que nous la connaissons. Il s’agit d’aborder les défis sociaux, politiques et environnementaux qui se posent face au développement humain excessif et l’épuisement progressif des réserves naturelles. Tout naturellement, Suchan Kinoshita propose de produire un troisième ensemble d’ « Isofollies ». Cette nouvelle constellation est bien évidemment produite in situ, avec les déchets et rebuts trouvés sur place. Né dans un dans un contexte domestique, temps compressé d’un lieu, recyclage du vécu de ses habitants successifs, le principe même de l’œuvre prend à Sharjah une signification augmentée et en quelque sorte planétaire.

Ces constellations successives agissent bien comme un espace de pensée à géométrie variable, du singulier au plus universel : Suchan Kinoshita a enfoui les rebuts d’une maisonnée, ensuite les résidus d’une production d’exposition, enfin un extrait condensé des déchets d’une mégalopole. Dans une quatrième déclinaison de l’œuvre, en 2014, elle a aussi enfoui les objets et souvenirs personnels d’une personne disparue, traces mémorielles qui acquièrent ainsi une nouvelle vivacité, abstraite et universelle. Rien n’est jamais figé dans l’œuvre de Suchan Kinoshita. Son travail protéiforme se développe sans cesse et se transforme avec les expériences accumulées. L’artiste considère chaque exposition comme le fragment d’un tout dont elle ne contrôle ni les limites, ni l’aboutissement. Bien que reliées entre elles par la volonté de l’artiste, les pièces dont elle est l’auteur s’enrichissent de connotations imprévues et peuvent se comprendre différemment selon les contextes spécifiques. Intéressant à cet égard est de considérer les divers moments et lieux où la constellation conçue à Sharjah est réapparue. Dans cette exposition dévolue à la « carrière du spectateur » (2009), certainement un job à temps plein, les quatorze éléments d’ « Isofollies », sont posés en contrepoint d’un monumental rideau de velours vert sur lequel, en poursuite, s’inscrit le halo lumineux d’un projecteur et derrière lequel tourne lentement sur elle-même une sphère à miroirs. Dans un rapport entre le tellurique et l’aérien, l’installation évoque une conjonction d’éléments qui renvoie à l’univers de René Magritte et ses mystères. Disposée en 2009 sous les voûtes du Pavillon de l’Horloge qui donne accès à la Cour Carrée du Louvre à Paris, « Isofollies » opère comme un chaos minéral face à l’ordonnancement classique des colonnes à cannelures érigées par l’architecte Jacques Lemercier au 17e siècle. Lors de son exposition « In ten minuten » (le temps est un paramètre essentiel dans l’oeuvre de Kinoshita) au Musée Ludwig à Cologne (2010) elles font face à cette autre œuvre que l’artiste nomme « Engawa », ponton en méranti, aux fines lattes de parquet ponctuées de lignes colorées et de petits carreaux jaunes, bleus et rouges, rythmé par une série de pilotis. L’engawa, dans l’architecture traditionnelle japonaise, est une passerelle de bois extérieure, un plancher surélevé, courant le long de la maison. C’est un lieu de passage, coiffé d’un toit pentu ; l’engawa module la relation entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur. On s’y arrête, on s’y assoit afin de contempler le jardin ou le paysage, on y médite. Ici, face à ce champ d’aérolithes qui rappelle l’épure totale du jardin japonais. Le « Sakuteiki », livre de conception du jardin, s’ouvre sur le titre de « L’art de disposer les pierres ». En 2011, lors de son exposition « The Right Moment at the Wrong place », au Museum De Paviljoens à Almere, elle concentre « Isofollies », dans un étroit et sombre réduit, retour à un obscur chaos des origines. Enfin, lors de l’exposition « Tussenbeelden » organisée à Schunck* (Heerlen 2014), le commissaire Paul Van der Eerden les compare aux « Bolis » de la culture Bambara, ces reliquaires manifestation de la force vitale dont la fonction principale est d’accumuler et de contrôler la force de vie naturelle. Ils contiennent des éléments divers, leur surface est sans cesse imprégnée de couches de libations. Pour l’initié, le « Boli » a une présence qui transcende l’objet lui-même ; objet réel dans un espace réel, il occupe aussi un espace mental dans la mémoire de la communauté.

3.

Cette fois les « Isofollies » de Sharjah sont mise en résonnance avec les travaux d’Aglaia Konrad. Et le dialogue s’instaure entre les œuvres des deux artistes, bien au delà du fait que les « Isofollies » de Suchan Kinoshita soient constituées de déchets provenant de l’une de ces mégalopoles qui sont l’un des principaux sujets d’observation et de réflexion inscrits au cœur de l’œuvre d’Aglaia Konrad. Celle-ci a inauguré en 2007, un vaste cycle de travaux – « Shaping Stones » et « Concrete & Samples » consacré à des architectures aux formes sculpturales. Dans « Sculpture House », l’artiste se saisit de la première maison belge réalisée en béton projeté, construite par l’architecte Jacques Gillet entre 1967 et 1968. Fruit d’une recherche de synthèse entre les dimensions fonctionnelle et esthétique de l’architecture, la maison est constituée de voiles de béton, offrant une multiplicité de points de vue qu’un seul cliché n’aurait pu rendre. Véritable sculpture que l’artiste nous fait découvrir par de lents travellings, le béton est ici puissance organique, la maison parfaitement intégrée avec la nature et les feuillages environnant, l’intérieur se prolongeant à l’extérieur et vice-versa. Konrad filmera ensuite toute la puissance brutaliste de l’Eglise de la Sainte Trinité (1976), chef-d’œuvre expressionniste de l’artiste autrichien Fritz Wotruba (1907-1975). Guidé par son approche tectonique de la sculpture de pierre, Wotruba réalise à Vienne une construction monumentale en misant sur l’empilement et l’enchevêtrement de gigantesques blocs de béton. La caméra d’Aglaia Konrad devient le meilleur témoin d’une architecture spirituelle unifiée dans le chaos, dont l’image primitive et atemporelle renvoie aux mégalithes sacrés de Stonehenge. Avec « Concrete & Samples II Blockhaus », elle en fera de même avec l’Église Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay de Nevers, conçue par Claude Parent et Paul Virilio. Monolithique, énigmatique, elle apparaît comme un bunker en béton brut. Ces recherches la mèneront aux carrières de Carrare dont elle photographiera et filmera le paysage minéral, ces montagnes de marbre, un paysage sans cesse en transformation qui paraît avoir été sculpté, comme une sculpture en creux dont on a extrait, au fil du temps, combien de chef d’œuvres qui jalonnent l’histoire de l’architecture et de la sculpture. Dans ses travaux plus récents encore, Konrad constitue un lapidarium de débris de constructions ; dans un même temps, elle indexe les pierres dressées du cromlech néolithique d’Averbury en épreuves imprimées sur papier baryté. Monolithes, mégalithes, force tectonique du béton brut, architecture organique ou brutaliste, pierre et sculpture, tout nous renvoie au rapport entre nature et culture, règne minéral et dynamique du vivant, chaos des origines et construction, du monde. « Avant que n’existent la mer, la terre, le ciel qui couvre tout, la nature dans l’univers entier ne présentait qu’un seul aspect que l’on nomma Chaos. C’était une masse grossière et confuse, rien d’autre qu’un amas inerte, un entassement de semences de choses, d’éléments divisés et mal joints », écrit Ovide dans ses « Métamorphoses »4. Les « Isofollies » de Suchan Kinoshita évoque les mêmes choses : le chaos des origines, la puissance minérale, l’inertie pétrifiante et la dynamique du vivant, le mégalithe et la sculpture, le recyclage et la métamorphose, la cosmogonie, la constellation et le chant de l’univers, les forces primordiales et la surabondance excessive, effrénée, inquiétante du monde actuel qu’elle recycle et réorganise telle une Titanide ou, plutôt, telle Sisyphe lui-même.

4.

Dans cette nouvelle série d’ « Undecided Frames » d’Aglaia Konrad, on pointera les vues aériennes, au dessus du désert de Gobi ou de la Sibérie, qui témoignent de l’organisation humaine, ces bardages métalliques qui semble peiner à contraindre le béton de cette tour à Mexico devant laquelle passe d’autant plus frêle chariot de plantes vertes, ces vues urbaines de Tokyo, de Chicago, de Hong Kong aux clichés si semblables et différents, la toute puissance du barrage de la Grande Dixence situé dans le Valais et dont l’architecture intérieure semble rivaliser avec les empilements et enchevêtrements monolithiques de l’église de Fritz Wotruba à Vienne. Le mouvement qu’opère l’objectif devant le barrage lui donne une dynamique plus grande encore, lui qui retient toutes les forces de la nature. On pointera également ces portes vitrées et miroirs photographiés à Porto. Aglaia Konrad semble chercher ici les seuils de singularités qui différencient les deux clichés quasi identiques. Il y a le lapidarium du musée archéologique de Cologne, Carrare bien sûr tout comme il y a également les choux de Créteil, ces tours brutalistes érigées par Gérard Grandval. Et on notera que le nom même de ces tours de béton nous renvoie à la nature.

1 Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp du Signe suivi de Notes, écrits réunis et présentés par Michel Sanouillet et Paul Matisse, Paris, Flammarion, 2008

2 Thierry Davila, De l’Inframince, Brève histoire de l’imperceptible de Marcel Duchamp à nos jours, Editions du Regard, Paris, 2010

3 Suchan Kinoshita, yukkurikosso yoi, galerie Nadja Vilenne, Liège, 2006. Collection Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht

4 Ovide, Métamorphoses, Trad. et notes de A.-M. Boxus et J. Poucet, Bruxelles, 2005

[sociallinkz]

La galerie participe à la 36e édition de ARCO Madrid, international contemporary Art fair et aura le plaisir de vous accueillir sur son stand 7B10

The gallery takes part in the 36th edition of ARCO Madrid, international contemporary art fair and will be pleased to welcome you on booth 7B10

Nous proposerons un duo d’artistes/ We will propose a duo of artists

AGLAIA KONRAD

SUCHAN KINOSHITA

36 INTERNATIONAL CONTEMPORARY ART FAIR

22 – 26 February 2017

Only professionals:

Wednesday 22 and Thursday 23, from 12 to 8 p.m..

Open to the public:

Friday 24, Saturday 25 and Sunday 26, from 12am to 8pm.

Official Inauguration: Thursday 23 at 10 am. By invitation of inauguration only.

Where:

FERIA DE MADRID

Halls 7 and 9

www.arco.ifema.es

[sociallinkz]

Suchan Kinoshita, Hok 1, 1996.

« How 1 » (Hutch 1) is the unpretentious title of this work by Suchan Kinoshita. It is a shelter build of waste wood. Inside you can find a laboratory with hourglass-like bottles in all colors of the rainbow. If you turn the hourglass (ask an attendant to do that for you) you can see and hear time ticking, dripping and sloshing. Meanwhile when you look outside you can see the day go by.

Illusion and Revelation

From the collection of the Bonnefantenmuseum

24.12.2016 – 27.11.2017

« Really good art is always relevant. Because it refers to possible worlds that are inextricably linked to our own. Because art gives shape to shapeless feelings and ideas, to revelations that would never have been revelations if not expressed, and to perceptions that would never have achieved that status if no shape had been found for them. »‘ – Quotation from Marjoleine de Vos in NRC, 30 October 2016.

We have always been fascinated by illusionism as a painting technique. Even the Ancient Greeks used optical illusions. Central perspective and its perfectionistic little brother the trompe l’oeil have been used since the fifteenth century to convince the viewer that the image in front of them is real and part of the same three-dimensional space that the viewer inhabits.

In modern society, digital technology is creating an illusionary layer of information that fits in seamlessly with our perception of the real world. It has become more difficult than ever to separate fact from fiction, genuine from fake.

Contemporary artists seduce us with visual worlds that can seem deceptively real and ordinary, but when we look closely they reveal a mysterious, ambiguous character. Sometimes there seems to be no logic to them at all.

It is inherent to artworks that they undermine our everyday, passive way of looking, stimulating and confusing us. At such a moment, our gaze is almost literally shaken loose from its customary thought patterns and associations, triggering a different mindset that may let us see a more truthful reality.

The exhibition Illusion and Revelation by Ernst Caramelle and the collection presentation also named Illusion and Revelation are on show in the Bonnefantenmuseum from December 24. The exhibition of Ernst Caramelle shows that the relationship between perception and visible reality is much more complex and ambiguous than we assume. This insight serves as the starting point for the focus in the presentation of works from the collection.

This collection presentation features art from the following artists:

Francis Alÿs / Monika Baer / Joan van Barneveld / Centrum voor Cubische Constructies / René Daniëls / Jan Dibbets / Peter Doig / Marlene Dumas / Bob Eikelboom / Hadassah Emmerich / Luciano Fabro / Lara Gasparotto / Nancy Haynes / David Heitz / Rodrigo Hernández / Thomas Hirschhorn / Pierre Huyghe / Duan Jianyu / Suchan Kinoshita / Sol LeWitt / Laura Lima / Mark Manders / Katja Mater / Tanja Ritterbex / Roman Signer / Lily van der Stokker / Joëlle Tuerlinckx / Emo Verkerk / William P.A.R.S. Graatsma / Kim Zwarts

[sociallinkz]

Suchan Kinoshita in :

Hinter dem Vorhang. Verhüllung und Enthüllung seit der Renaissance. Von Tizian bis Christo

Hrsg. Beat Wismer, Claudia Blümle

Gebunden, 340 Seiten, 297 Abbildungen in Farbe, 24 x 30 cm

Jacques Lizène et Jacques Charlier in :

Liesbeth Decan

Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial

Photo-Based Art in Belgium (1960s – early 1990s)

Leuven University Press

ISBN: 9789462700772

The role of photography in Belgian visual art

Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial is the first in-depth study of the use of photography by Belgian artists from the 1960s until the early 1990s. During these three decades, photography generally underwent a major evolution with regard to its status as a gallery-focused fine art practice. Liesbeth Decan explores ten representative case studies, which are contextualized within and compared with contemporary international artistic trends. Successively, she addresses the pioneering use of photography within Conceptual art (represented by Marcel Broodthaers, Jacques Charlier, and Jef Geys), the heyday of Photoconceptualism in Belgium (represented by Jacques Lennep, Jacques Lizène, Philippe Van Snick, and Danny Matthys), and the transition from a conceptual use of photography towards a more pictorial, tableau-like approach of the medium (represented by Jan Vercruysse, Ria Pacquée, and Dirk Braeckman). Ultimately, the selected case studies reveal that photo-based art in Belgium appears to be characterized by a unique uniting of elements particularly from Conceptual art, Surrealism, and the pictorial tradition.

Jacques Lizène in :

Denis Gielen

REBEL REBEL ART + ROCK

Author: Editor: Denis Gielen. Authors: Denis Gielen, Jeff Rian, Julien Foucart

Hardback, 300x215mm, 304p, 300 colour illustrations,

French edition

Fonds Mercator/ Mercatorfonds

ISBN: 9789462301498

Depuis les années 60, le rock fait partie, avec d’autres cultures populaires comme la Science-fiction, des nouvelles sources d’inspiration et de réflexions que détournent les artistes plasticiens. Dérivé du blues et de la country, musiques rurales américaines, le rock qui apparaît à la fin des fifties se profile comme une culture typiquement adolescente dont l’histoire oscille entre divertissement industriel et révolte suburbaine. Célébrée avec nostalgie ou parodiée avec virulence, sa « religion » hante, depuis le Pop Art, tout un pan de l’art contemporain de ses distorsions électriques et refrains diaboliques. Associé à l’art, il élargi le spectre d’une sensibilité désormais partagée : de la révolte politique à la crise identitaire en passant par le nihilisme artistique.

Publié à l’occasion de l’importante exposition Rebel Rebel (Art + Rock) programmée par le MAC’s au Grand-Hornu, en 2016, cet ouvrage propose une traversée de l’art contemporain à travers le prisme du rock et de ses trois principales facettes. Colorée notamment par les chansons de Hank Williams ou Patti Smith, la première met en lumière des artistes qui, comme Dan Graham, Allen Ruppersberg ou David Askevold, se sont interessés aux racines vernaculaires de la musique rock. La seconde, iconique à l’image d’Elvis Presley, Deborah Harry ou Kurt Cobain, sélectionne des oeuvres qui s’en prennent aux vanités du star system et de son esthétique glamour, à la manière de Mimmo Rotella, Douglas Gordon ou General Idea. Enfin, teintée par la noirceur de groupes punk comme les Ramones ou les Stooges, la troisième facette du rock présente des plasticiens iconoclastes qui déconstruisent, comme Art & Langage, Steven Parrino ou Jonathan Monk, le mythe moderniste de l’auteur génial. A chacune de ces facettes correspond un chapitre du livre qui, partant de duos ‘art-rock’ (Andy Warhol + Bob Dylan, Tony Oursler + Sonic Youth, Jeremy Deller + New Order,… ), s’organise en divers planches iconographiques. Augmentées de biographies, d’une chronologie et d’un glossaire, ces trois parties respectivement intitulées Roots, Looks et Fools constituent le coeur d’un projet éditorial où musique rock et art contemporain s’associent en un combo bâtard et rebelle.

Aglaia Konrad in :

Aglaia Konrad

From A to K

L’ouvrage Aglaia Konrad From A to K, d’après une idée originale de l’artiste, a été rédigé par Emiliano Battista et Stefaan Vervoort. Conçu et présenté sur le modèle d’une encyclopédie, il propose une large sélection d’images inédites, tant en couleurs qu’en noir et blanc, accompagnée d’un glossaire classé par ordre alphabétique dont la présence organise et structure l’ouvrage.

Cette liste reflète l’intérêt que l’artiste porte depuis longtemps aux dimensions changeantes des environnements publics et privés tels qu’elles se manifestent dans l’architecture, l’urbanisme et la ville dans son ensemble. De plus, le glossaire rend explicites le processus d’élaboration de l’ouvrage et les choix qui y ont conduits, comme s’il s’agissait d’un répertoire des nombreuses idées qui l’ont inspiré.

Les textes répartis à travers Aglaia Konrad From A to K portent tous comme titre une expression sélectionnée dans le glossaire, dont « (pre-)Architecture », « Book », « City », « Concrete » et « Elasticity ». L’ouvrage comporte des essais et des témoignages personnels de Friedrich Achleitner, Hildegund Amanshauser, Elke Couchez, Penelope Curtis, Michiel Dehaene, Steven Humblet, Moritz Küng, Spyros Papapetros, Angelika Stepken, Edit Tóth et des rédacteurs, ainsi que des contributions des artistes Koenraad Dedobbeleer et Willem Oorebeek.

Emiliano Battista & Stefaan Vervoort (réd.), Éditions Koenig Books, Cologne, 391 p., uniquement disponible en anglais.

[sociallinkz]

Suchan Kinoshita

Meaning is moist, 2006

Mixed media, 180 x 140 x 270 cm

Behind the curtain. Concealment and Revelation since the Renaissance. From Titian to Christo, Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf

The starting point of this exhibition is the tale of the contest between two ancient painters, who sought to outdo each other’s virtuosity in the art of trompe l’oeil. While Zeuxis, however, was merely able to fool the pigeons, which attempted to peck at the grapes he had painted, Parrhasius succeeded in actually deceiving the eye of his rival, who attempted to draw the curtain painted by Parrhasius to reveal the picture assumed to be behind it.

The fascinating interplay between concealing and showing, veiling and revealing using a curtain, veil or drapery is introduced in this themed exhibition, which is staged exclusively in Düsseldorf and shows important works from six centuries. With loans from international museums and private collections – paintings, drawings, sculptures, installations and photographs – the show ranges from Renaissance and Baroque paintings to modern and contemporary art. Alongside Titian’s “Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto” dated 1558, which is on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition includes works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, El Greco, Jacopo Tintoretto, Arnold Böcklin, Robert Delaunay, Max Beckmann, Cindy Sherman, Christo and Gerhard Richter.

The exhibition, which is curated by General Director Beat Wismer and Claudia Blümle, Professor at the Institute of Art and Visual Studies of Humboldt Universität in Berlin, illuminates in different thematic chapters the ambivalence and fascination surrounding the notion of concealment and revelation, as well as the relationship between the fine arts and perception. The wealth of topics covered start with the antique painting competition and in further chapters turn to issues such as “mystery of the divine”, “power of representation”, “violence of unveiling”, “thrill of the concealed”, “internal and external”, as well as “the art of unveiling”.

The exhibition, which spans several epochs and genres, not only draws a link to the present in terms of the choice of works presented. To this day, the veil, concealment and revelation play an important part in religious and social contexts, as well as in fashion. In the same vein as the curtain, far more than any other motif, mediates between the world of the viewer and that of the picture, the programme accompanying the exhibition is intended to open up further spheres of experience to visitors.

Museum Kunstpalats, Düsseldorf > 22.01.2017

[sociallinkz]

Suchan Kinoshita

Meaning is moist, 2006

Mixed media

Suchan Kinoshita participe à l’exposition « Behind the curtain. Concealment and Revelation since the Renaissance. From Titian to Christo » qui se tient au Museum KunstPalast à Dusseldorf du 1er octobre au 22 janvier 2017

Set against the background of the legend of the origin of mimetic painting – the tale of the contest between the ancient painters Zeuxis and Parrhasios – this thematic exhibition takes a look at the motifs of veil and curtain, thus illuminating fundamental issues of painting and fine art in general. The exhibition demonstrates the interplay between showing and concealing, revealing and veiling with a range of exclusive loans of art. The works range from Renaissance and Baroque paintings to modern and contemporary art. Alongside the key work of the exhibition, Titian’s “Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto” from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Museum Kunstpalast presents a variety of loans from international museums and private collections, including works by Giovanni Bellini, François Boucher, Max Beckmann, Arnold Böcklin, Robert Delaunay Gerhard Richter. The exhibition is curated by General Director Beat Wismer and Claudia Blümle, Professor at the Institute of Art and Visual Studies of Humboldt Universität in Berlin.

Die Ausstellung widmet sich anhand der Motive Schleier und Vorhang Grundfragen der Malerei und der bildenden Kunst. Das Wechselspiel zwischen Zeigen und Verbergen, Enthüllen und Verhüllen wird durch hochkarätige Leihgaben internationaler Museen verdeutlicht – von Tizian über Rubens bis Gerhard Richter, von der Malerei der Renaissance und des Barock über die Kunst der Moderne bis hin zur Gegenwart.

[sociallinkz]