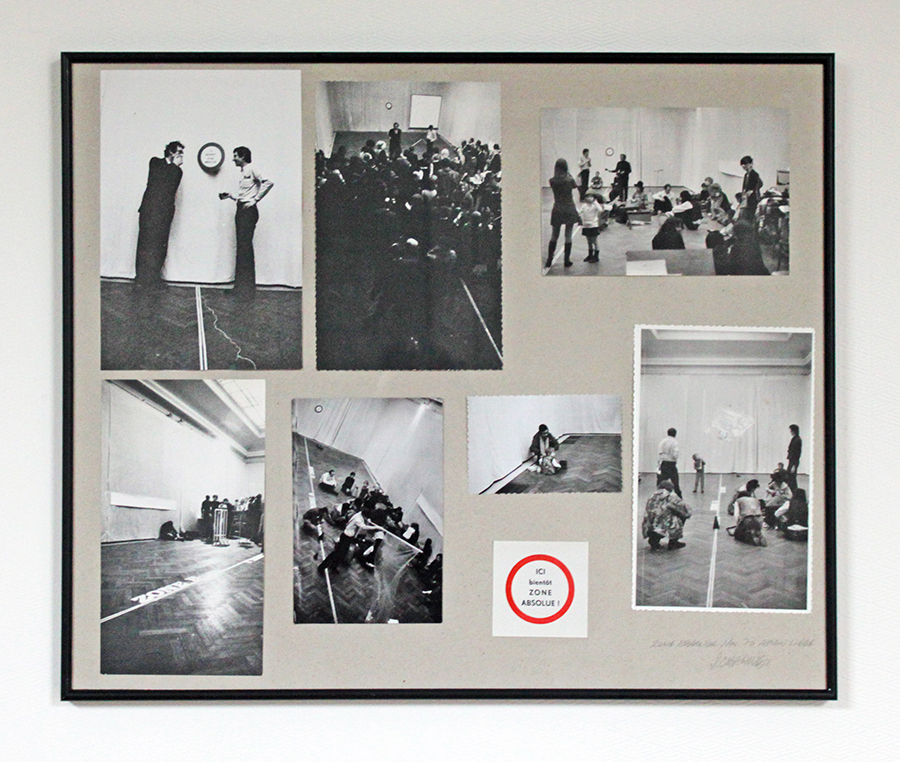

Jacques Charlier

Zone Absolue, 1969-70

photographie NB, impression sur toile, 100 x 120 cm

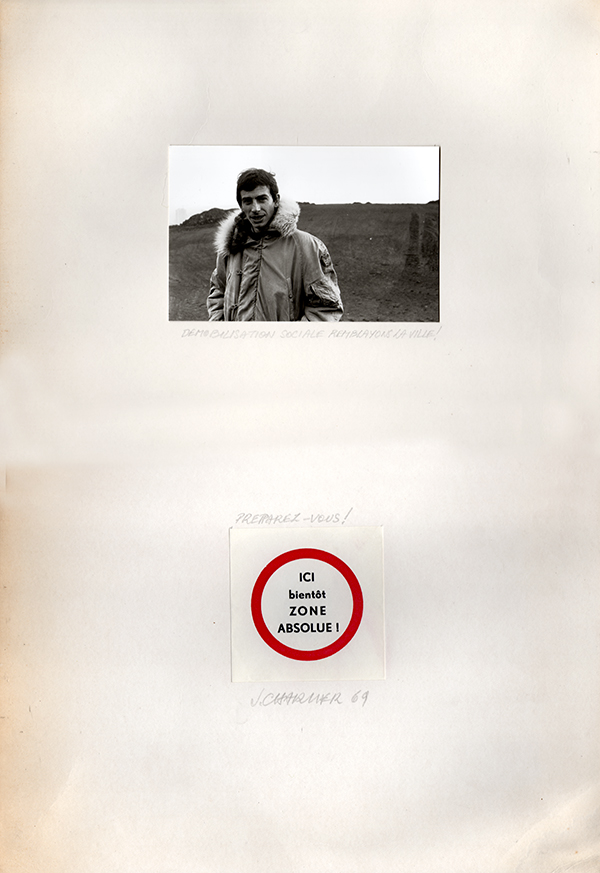

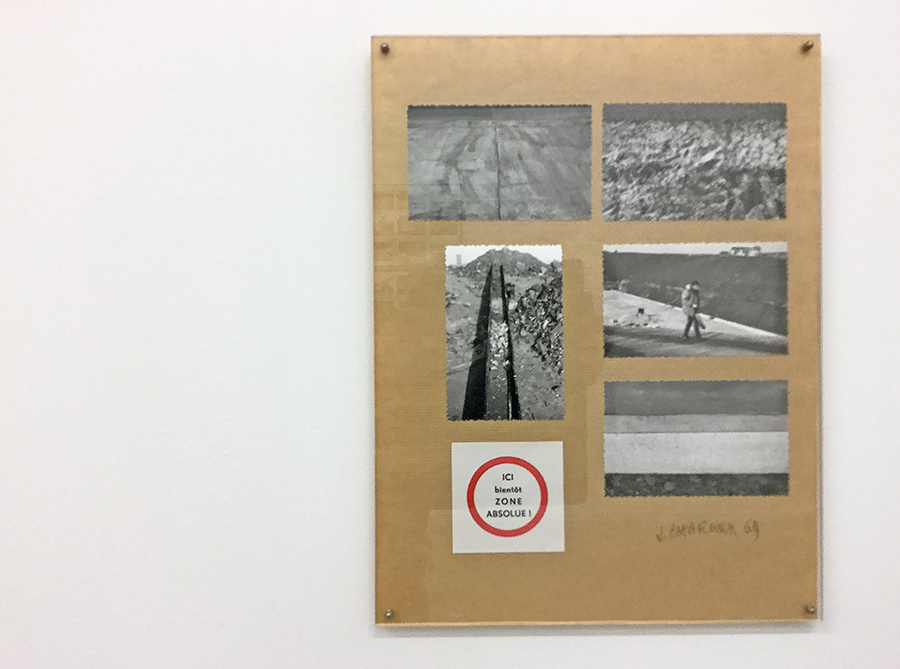

Jacques Charlier

Zone Absolue, 1970

photographies NB et autocollant, 60 x 70 cm

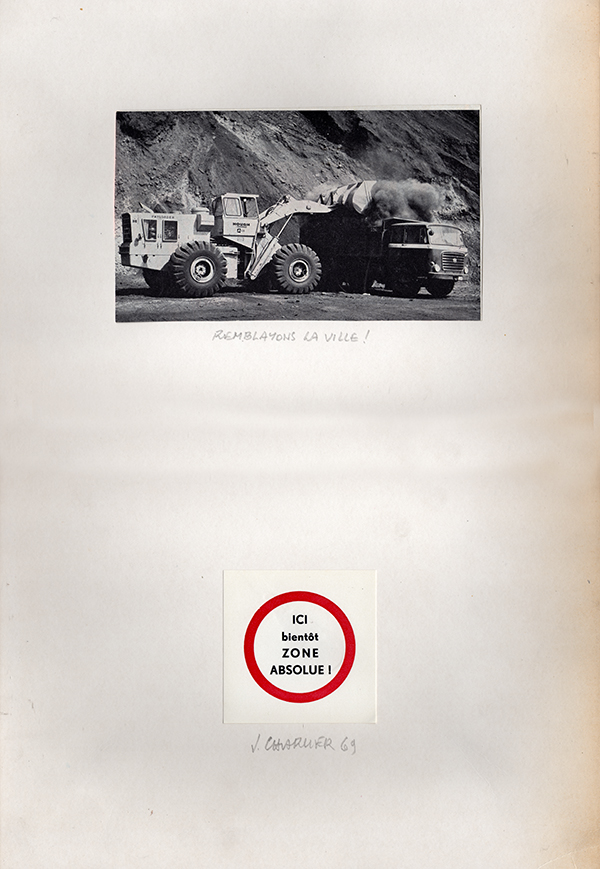

Jacques Charlier

Zone Absolue, 1969

Collection privée

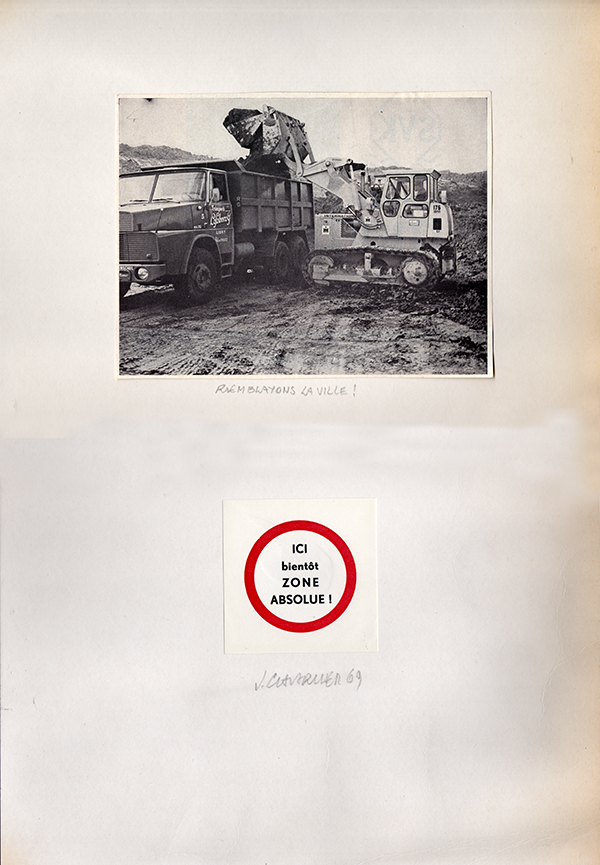

Jacques Charlier

Zone Absolue 1970

Photographies NB et autocollants, (9) x 54,5 x 47 cm

Jacques Charlier

Zone Absolue, 1969

photographies NB et autocollant, 50 x 40 cm

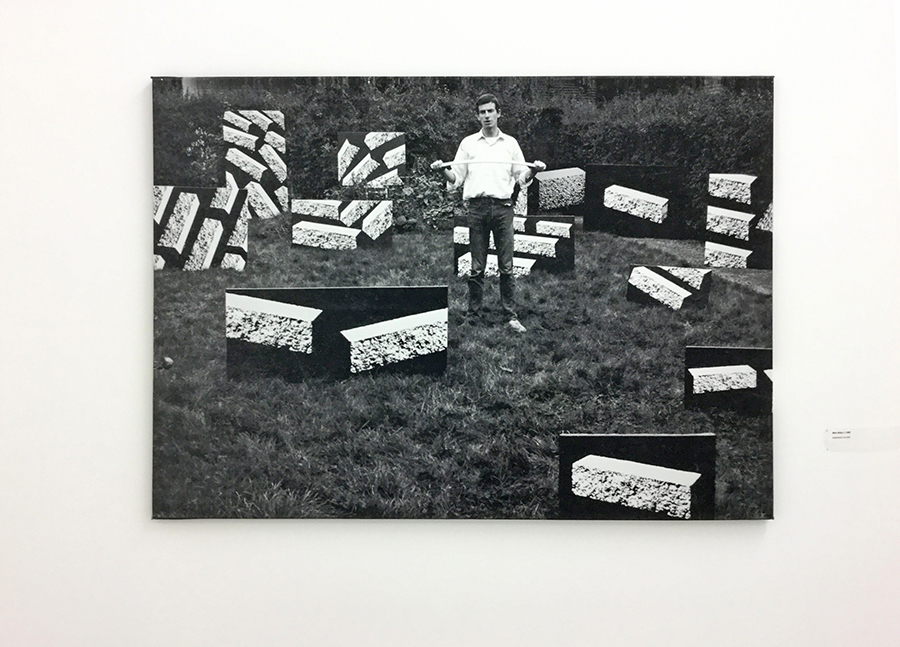

Jacques Charlier

Tableau béton, 1968

photographie NB impression sur toile, 100 x 120 cm

(…) – Let’s just say that in these days, I try to paint in every style, for every time I have an idea, I try to go about it in the style best suited for it. I have to admit that the hardest part of my work, the professional photographs, doesn’t make it. Marcel Broodthaers, to whom I show them, doesn’t really encourage me; he claims it’s very hard. Sonnabend just doesn’t want to hear about it. The reason is simple: there is no intervention from the artist in those works. Despite the fact I had such a great, well substantiated theory to explain that those photographs were the absolute opposite of the found object, the critics didn’t care. I had already plotted my Absolute Zone plan, some sort of urbanization full of concrete, some sort of satire of urbanization. The strong point, for me, was the highway project that was supposed to go through Liège, the senseless scale models made by “urbanization believers” and that they show to the public, this urban delirium. I show the plan to Marcel Broodthaers, who looks at me as if I had fallen on my head, and very realistically advises me to make a series of tableaux on the theme of concrete instead. He even promises to find me a buyer. I therefore find a nice block of concrete in a technical journal and I paint on fifteen or so canvas of every size blocks of concrete in every position. Yvan Lechien, who held the Cogeime gallery in Brussels, sees them and, surprise, buys them.

– It’s the “Blocks” exhibition in 1969 in Brussels?

– Yvan Lechien exhibits my tableaux, moreover selling most of them. It was a surprise. Broodthaers takes advantage of it to introduce me to a few Brussels based avant-garde spirits, Marie-Jeanne and Jean Dypréau, Fernande and Jacques Meuris, Marcel Stael, Jean Ley, Isy Fiszman, Nicole and Herman Daled, Jean-Pierre Van Thiegem, Denise and Karel Gerilandt, Betty Barman… following this exhibition, I tried to convince Yvan Lechien to go farther and create an Absolute Zone since he had already shown the propaganda paintings of that concrete universe that’s invading us. I, for myself, draw pipelines; Yvan Lechien shows a little more interest for this work, but Absolute Zone is a no go.

– You have accompanied this plan, drawn in 1968, by a kind of founding text that will be published in 1983 attached to the book “Dans les règles de l’Art”, a text whose title was “What is the concrete-urbanization of a city? How to realize it?”. In that text, you propose to “solve in a savage and extreme way the problems of housing and traffic in the cities”. There is a number of methodological recommendations: the psychological conditioning of the average citizen, the use of evening classes on how to mix concrete, the overall mobilization of the entrepreneurs. You add a description of the tasks: systematically filling the sewers and pipelines, pouring concrete on historical monuments and folk statues, building barricades made out of concrete on the road accesses to the city and, finally, concreting the city. It’s perfectly delirious. In addition, you institute yourself as Director of the operation and create a Research Committee on Absolute Zones’ establishment.

– Absolutely, I declare myself Director of the Absolute Zones. It’s the time of poetic appropriations. Marcel Broodthaers will soon afterwards become Curator of the Musée des Aigles, Filiou takes care of his Poïpoïdrome, Ben creates his gallery, Panamarenko moves around wearing his military uniforms, and let’s not talk about Beuys or his office in Düsseldorf. I, however, only became Director of the Absolute Zones as part of this work. During the 70s, I did it again, instituting myself as the Director of the C.I.D.A.C., a centre devoted to the dangers and the toxicity of art, a detoxification structure copied on Alcoholics Anonymous. How does someone get detoxified from art and from the addiction to creation? In fact, another inverted satire. Inventing such a role means creating for yourself an underground world, parallel to reality, reaching a pseudo-legitimacy.

– This project of Absolute Zone, what is it, beyond this delirious fiction of the all concrete. How do you see it?

– Reading this situationist, anarchist literature, everything I receive by mail ends up calling to me through its artistic side and its meaning through time. I end up wondering if we shouldn’t reconnect with a form of collective art, with extremely simple things that can make us think about the world, like some sort of symbolic criticism.

I look at this urban inrush with a very critical eye, but at the same time, I do the same with some ecological ideologies advocating nature every time they can, a return to primary agriculture, the “all natural”, a fantasy fashionable at the end of the 60s. I’m therefore seeking to create an object that would be like a symbolic and critical picture of those two extremes. I envision this: let’s put a slab of concrete, which is the transposition of my professional universe, those slabs of concrete making the roads and the works of art. It’s the A zone, like a piece of road. Besides it, let’s demarcate a piece the same size of agricultural zone, with good ground. It’s the B zone. On D day, the day of inauguration, we invite the public to come plant in the B zone, anarchically but under notary convention, vegetables as well as trees or flowers. The protocol I imagine is the following: those two zones will coexist as a sculpture. Through the years, the concrete will suffer the ravages of time. And the natural zone will grab its territory anarchically, because it is stipulated, to heighten this naturalistic and nostalgic fantasy, that the hand of man will not domesticate, will not negotiate this Absolute Zone. It will stay absolutely natural in its progressive entanglement. Both fantasies will therefore last side by side.

The Absolute Zone is like twin zygotes. They always have the same size, but their materials are totally antagonistic. Like with fraternal twins; they are totally identical and totally different. We always have some sort of fascination for the double. Warhol understood it, Magritte before him too. This fascination with twins have always existed, from Rome’s foundation to the destruction of the WTC towers. On one of Total’s covers, I drew two angels, “Total’s energetic”; they are copies each one of the other. It’s the monozygotic universe that can reflect only itself, indulging like Narcissus facing its physical double.

– Was it a way to imagine environmental art, land art or minimalism in a critical fashion? A minimal concrete slab in a landscape, would it be like environmental art?

– There is also in nature a space for critical thinking. I knew all the positions of Land Art then. In fact, like a lot of people, I knew them through the photographic renderings made of them, those clean photographs of Land Art works people placed in art galleries. You have to admit people very seldom take a walk where those works are conceived; those photographs telling their tales end up into collectors hands: they are like a new school of Barbizon. I find this type of sculpture and investigation interesting both from the plastic and art history point of views, but I feel no evocation of critical thought, nor political point of view. To propose an Absolute Zone in the urban universe, to do as if it was a section of road, to juxtapose to it this vegetal area that will stay raw, but created by the people, this becomes a collective gesture, all of this inducting an area of intention that’s not purely aesthetic, but it also criticizes the times in which we live. It was, somehow, a fracture with what was happening in the galleries; it was also a direct take on my professional universe. There was some kind of a blending. People often blamed me then for having no unity of style in my works, for using varied mediums, for being at the same time involved in the system of art and away from it, as if I was running in circles around it. I had — and the paradigm of that idea will nonetheless slowly appear to the eyes of some people — the intent of criticizing art, like I had the intent of criticizing urbanization and the delirious fantasies it was then possessed of. I had the same intent to criticize ideologies, facing the effects of those mainstream truths, including those of this burghers’ pseudo-revolution. I repeat it, even though I found some good ideas in the movement of 68, I was shocked by those revolutionary daddy’s boys invading the factories and the working class they didn’t know anything about. I was the son of a worker, I had to draw road projects to live. I picketed during the strikes of the 60s.

– In march 1968, you wrote a short text perfectly illustrating those words, a text destined to accompany a series of pictures. I quote you: “This series of press clipping has been taken from public works journals that reached the S.T.P. of Liège. Those press pictures are somehow professional publicity shots, boasting about the merits of drain technology. Their enigmatic character can not only rival with a few contemporary plastic researches, but surpass them through their tremendous expressive capabilities. But this is something no one will ever say, or maybe they will but too late. Thus today’s art, under the guise of esoteric creation, distracts for its own purpose the reality of work, unbearable to the dominant cultural minority”.

– This photo series has been made into a slide show to be projected over the super 8 film “underground pipelines” at the Absolute Zone exhibition. Yes, those pipelines are the fruit of the labour. At that time, I’ve been flabbergasted by Bernd and Hilla Becher’s positions, among others. I’m thinking of a text from Carl André written on their “anonymous sculptures”. This proclaimed anonymity mocks the social reality of the objects photographed.

– Let’s get to the exhibition itself. What do you show in it?

– This exhibition is also the fruit of a dilemma. It develops at a time when people responsible for the Apiaw, the association for intellectual and artistic progress in Wallonia, a major group with, among others, the function of telling what was happening in Paris. This association is pushed aside by the movement of 68. We must not forget the Academy of Liège has long been occupied, an occupation I don’t participate in despite pressures from Marcel Broodthaers, who was conducting the occupation of the Palais des Beaux-Arts of Brussels. Broodthaers tells me we have to occupy the Aca, he even adds he’s going to join us, that I need to prepare an action, to go there with Total’s transparent flag. My wife, Nicole Forsback, knows the context; she’s just out of the engraving workshop of the Academy. Until the day before the action, I’m somewhat divided. I’m seduced by the efforts of some, Nyst, Yellow, Lizène, but I’m telling myself it is still marginal, that an invasion of the insides of the academic system wouldn’t breed a new academism. In short, I didn’t go. End of 69 then, the steering committee of the Apiaw prefers to let go and to leave the programme to a group of artists from Liège. I remember two meetings held in a brewery in the city centre. From the first vote, they choose me for the next exhibition. I’m very surprised. Of course there are disagreements, but a second vote confirms it. I go further by declaring to the assembly that M. Schoefeniels has to be told I want to be the master of the place, for I want to make an exhibition completely different from what “they” expect. For better or for worse, this assembly just wanted me to turn this into a provocation. Since I had my Absolute Zone plan in my boxes, I thought it would be the right moment to show it.

If I remember correctly, Léon Wuidar had the exhibition before mine. At least I have a blurred memory of him being there when I carefully swept the floor to put squarely in the middle two strips of white tape, therefore splitting it in two equal areas. This double strip foreshadowed the zones A and B, the areas to be covered in concrete and on which to plant, like a plan of what could happen on a real scale. On the back wall, in view of this double strip, a red and white signpost: “Here soon Absolute Zone”. On one of the two picture rails, just stuck on two wooden bars, the long drawing of the Absolute Zone. I refer to it as the most collective work there is: place a strip on the equator and thus demarcate the most complete absolute zones, North pole side, all concrete, South pole side, all vegetation. On the wall, more drawings and graphics: a plan for the establishment of an absolute zone in Liège, another to make one in the Apiaw room. (..)

– On another document, we see you with Marcel Broodthaers, standing on both sides of the demarcation of the Absolute Zone.

– Marcel, learning that the exhibition would happen, offers to do the opening. Magnificent! Broodthaers is eloquent and he’s from Brussels. It’s perfect for me. I thought he would make a superb presentation of my Absolute Zone; I was expecting a speech.

– De facto, the photography shows Marcel Broodthaers standing in the middle of the room, hands behind his back, somehow in the attitude of a condottiero. And the public, standing tight, facing him at some distance.

– The public had some trouble entering the exhibition. For a while, they just stayed tight at the bottom of the room. Marcel Broodthaers stands very far, trying to bring them closer. He’s nearly under the Absolute Zone sign. I was expecting a speech. Well no. Marcel just said a few words, declaring that my work was actual and it was a must see at this time. He finishes with a simple toast: “Cheers”!

The pressure in the room was terrible, some sort of fear, a total lack of understanding, even greater since even before its opening the exhibition had made such a fuss in the whole city. It was awaited. With the Total’s group, we had advertised it in every possible way. At the cinema, they were showing Z, the 1969 Costa-Gavras’ film. In town, there were therefore posters of the Z film everywhere. We outdid them by painting “Z” on public buildings and by turning the Z of the posters in Absolute Zone.

– Nice coincidence since Costa-Gavras’ film denounced a totalitarian regime, the one of the Greek colonels.

– Yes, yes. We also stuck our posters “CivilizaTion” with the totalitarian T. Even better, at night with Philippe Gielen we traced a demarcation line of the Absolute Zone in the middle of the city. I still remember sitting with paint cans in the trunk of Gielen’s minivan. He was driving around the block and I was discharging, can after can, a long coloured line on the street. It wasn’t dry in the morning. The “effects” created by car tires were… surprising. We went at it hard… I received a call from Robert Stéphane telling me to “order my people to stop” after we painted the front of the RTB. Schoefeniels and Jacques Parisse, responsible for the Apiaw, have been called to the police… In any case, the evening of the exhibition, the public is puzzled, even scared. The evening will end in tremendous libations. The people were so disturbed by the situation that they just drank. Schoefeniels was furious, he called me asking “Do you think I pay heating bills for empty walls?”.

The provocative side of the exhibition’s aesthetic even takes more importance than its content. People understand next to nothing of what I’m saying. It’s put away with the hardest of conceptual art or theoretical Land Art. In any case, it’s all drowned except for a few, the Totalitarians, the Jazz Crapuleux band, those visiting the Yellow gallery that will soon become a cutting edge gallery. Antaki was there, Richard Tialans, Alain d’Hooge, Jacques Lizène, Michel Lhomme, Sangier… later in the evening, Broodthaers tells me he would also like to exhibit in this Apiaw room, that this association has a nice tradition. I tried to introduce him to Schoefeniels and to explain Marcel’s work. Schoefeniels says “Oh, no, that’s enough! No mussels pans here!”. Broodthaers will not exhibit in Liège, at least not right now. There will be some sort of a feeling of regret later on: Robert Stéphane and Annie Lummerzheim will organize a small exhibition “Broodthaers, Christiaens, Charlier” in the RTB rooms. At the exhibition, there will be five of us, yelling loudly.

Translation of Jean-Michel Botquin & Jacques Charlier, « Zone Absolue, une exposition de Jacques Charlier en 1970 », Editions L’Usine à Stars.

[sociallinkz]