Lu dans l’Art Même, Automne 2024

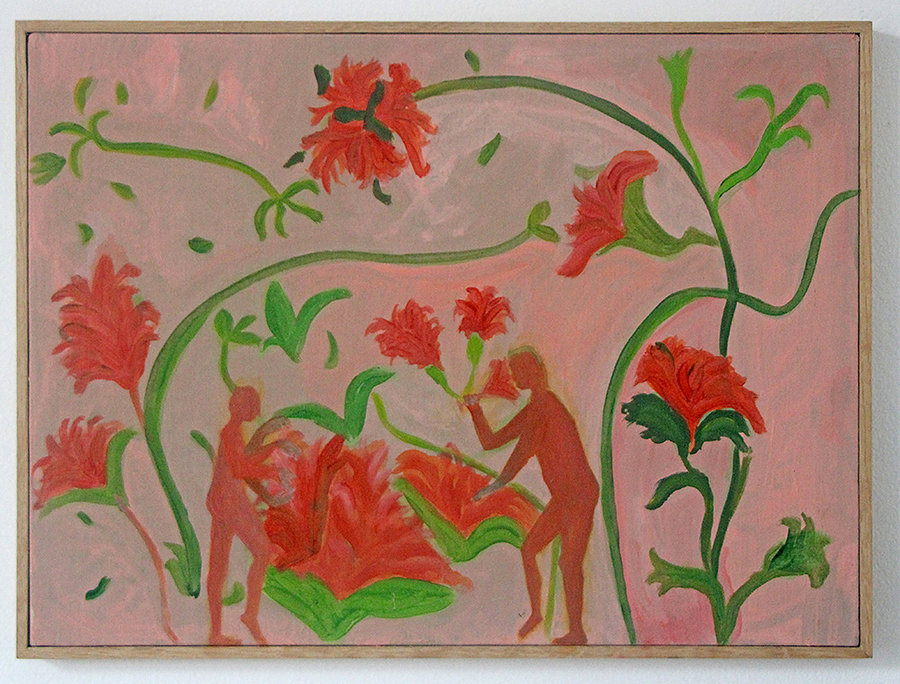

One of ltalo Calvino’s ‘Six Memos for the Next Millenium’ is concerned with the question of ‘lightness’. Quoting the De Rerum Natura of Lucretius, he muses on the idea that knowledge of the world tends to dissolve its solidity, leading to a perception of ail that is infinitely light and mobile. He talks, too (for these essays were conceived as lectures), of ‘the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness. Lucretius, he tells us, is a poet of the physical and the concrete, who nonetheless proposes that emptiness is as dense as solid matter. Just so, as lightness is inseparable from precision and determination. ‘One should be light like a bird, and not like a feather’, said the poet Paul Valéry.

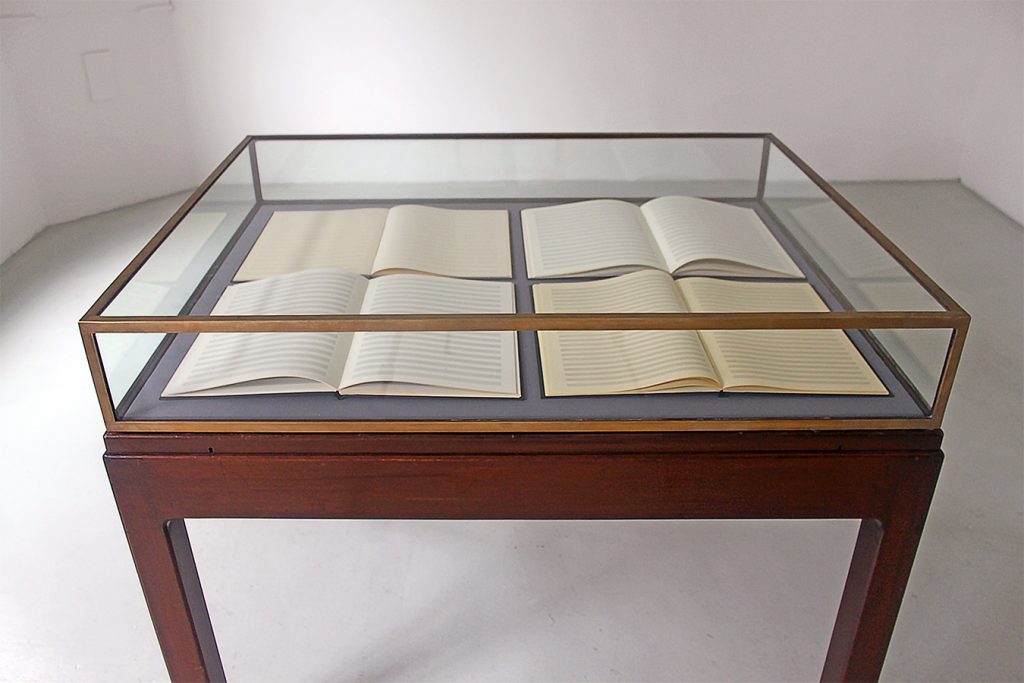

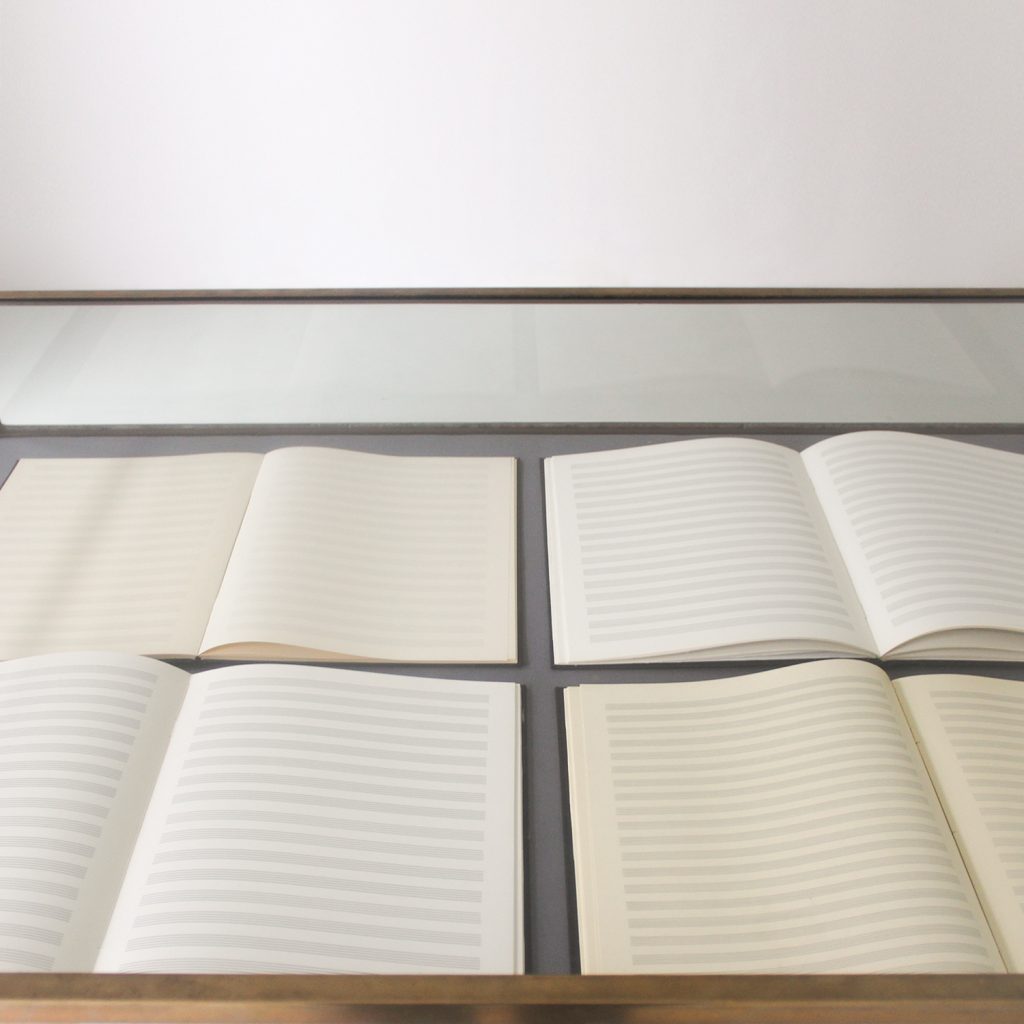

If lightness has to do with the subtraction of weight, then this body of work by John Murphy is light. Several of these canvases carry merely the delineation of an ear; the others refer to the state of being that remains when all weight has been removed. ‘Selected Works’, blank music paper bound and displayed in vitrines, push that liminal state a step further into the unknown, for they exist in a permanent state of potentiality, somewhere between birth and death.

A point of entry into this weightless world may be through ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Deaf Man’, a recent work based on a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. To those who are in possession of all their senses, the condition of deafness, like that of blindness, can suggest both isolation and an acute awareness of an inner world. ln conjunction with ‘Selected Works’, are we to suppose that the artist, within himself, hears echoes of Baudelaire’s « La Musique », which was inspired by the work of the deaf composer, Beethoven? (‘l feel all the passions of a groaning ship vibrate within me, the fair wind andthe tempest’s rage cradle me on the fathomless deep- or else there is a fiat cairn, the giant mirror of my despair’). But perhaps he can hear nothing at all?

There is solitude in John Murphy’s work, as well as a little irony and a touch of the comic. (Calvino, again, remarks that ‘melancholy is sadness that has taken on lightness. Humour is comedy that has lost its bodily weight’). The space in these paintings is unidentifiable; it is neither close nor distant. So, too, is their colour, which is poised but unstable. Pink passes into blue; blue passes into pink.

Music and the metaphysical are seldom far apart. It is in and through music that many of us feel most intimately in the presence of meaning that cannot verbally be expressed. Murphy’s ‘Selected Works’ are either so full of meaning that they are inexpressible or, quite plainly, they have never existed. Like his paintings, the ‘Selected Works’ invoke the aesthetics of the sublime; they present the unpresentable to demonstrate that there is something conceivable which is not perceptible to the senses. The experience of the sublime, according to Kant, accords us simultaneous grief and pleasure, because it both opens and conceals. The sublime impedes the beautiful; it destabilizes good taste.

Francois Lyotard, who has written about a connection between the aesthetics of the sublime and postmodernism, suggests that it is the business of contemporary culture to invent allusions to the conceivable that cannot be presented – not to enjoy them but to impart a new sense of the unpresentable. Calvino makes a comparable point, more wonderfully. ‘Think what it would be like to have a work conceived from outside the self, he writes, ‘a work that would let us escape the limited perspective of the individual, not only to enter into selves like our own but to give speech to that which has no language, to the bird perching on the edge of the gutter, to the bee in spring and the tree in fall, to stone, to cement, to plastic… ‘. John Murphy conveys to us the activity of absence – its force and inner vitality.

John Hutchinson

Dublin, August 1996.

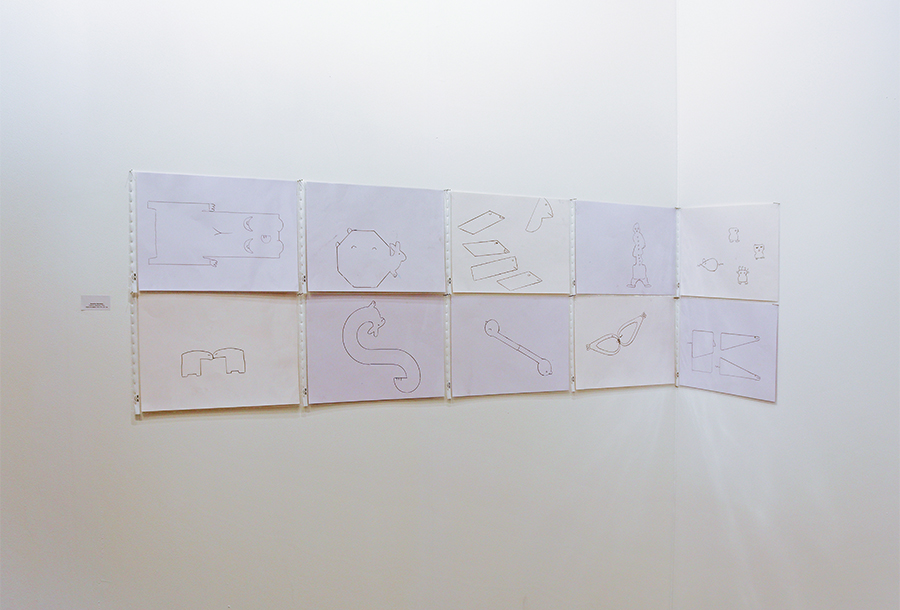

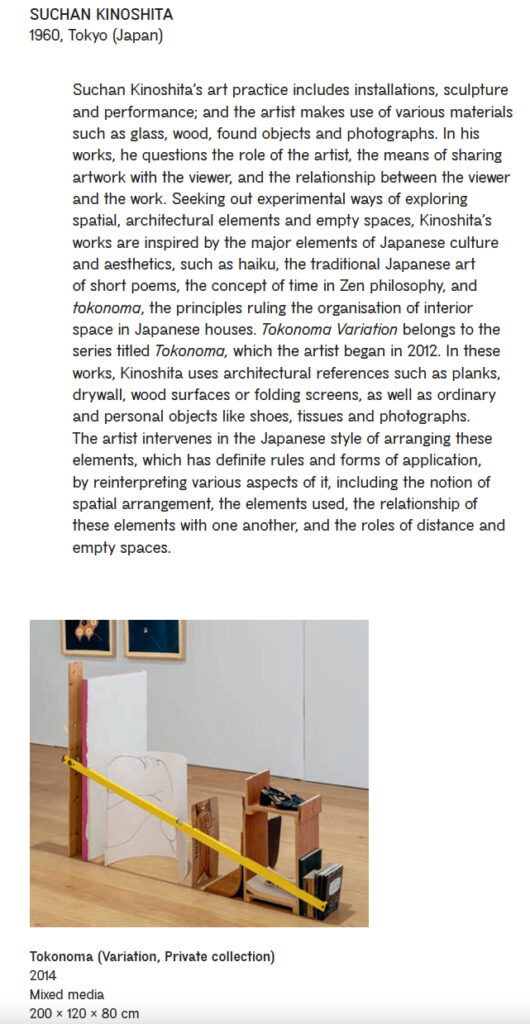

By titling her exhibition “Architectural Psychodramas,” Suchan Kinoshita effectively provides the salient keywords that lead to a possible mode of reception. Kinoshita invariably eschews fixed categories and definitions; she loves the changeable and the speculative. For her, architecture is built space, environmental space that influences us, but also some- thing that we shape. “Psychodramas,” experiences, memories and emotions stick to it, but without necessarily congealing; they remain changeable. This understanding of time and space, replete with the subject-object groupings and contexts of meaning that are constantly updated within it, also resonates recognizably in her background in music and performance art. The individual elements in the exhibition are not given one single role or meaning. Rather, it is about their “potential as objects,” as Eran Schaerf described it in the catalogue for Kinoshita’s exhibition at Museum Ludwig, Cologne (2010). As a result, there are countless connections to be discovered between the totality of the assembled elements, which coalesce and condense in a number of themes and ideas, no sooner to jump into another context once more. (…)

Suchan Kinoshita produce sounds with the help of birdcalls. She presents them via instruments, made with by hand and with incredible creativity, in a kind of aviary, thus also adhering to the principle of granting a physical presence to the acoustic components of the exhibition. These objects, too, are architectures in Kinoshita’s understanding, since they form a dwelling place for sound. And this brings us back to the never-ending topic of change- ability: when Kinoshita deploys birdcalls, it is by no means to imitate them. Instead, it is about the creation of something new. Just as it is with every memory, every object, every word.

Kristina Scepanski, introduction to the exhibition « Architektonische Psychodramen » Westfälischer Kunstverein, 2022.

L’asbl La Jeune Peinture Belge a annoncé le nom de la lauréate du BelgianArtPrize 2025. Suchan Kinoshita a été sélectionnée par le jury et invitée à créer et à présenter de nouvelles œuvres au Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles / Bozar du 24 avril au 29 juin 2025. Le BelgianArtPrize est le prix d’art contemporain le plus connu en Belgique. Son objectif est de soutenir les artistes belges ou les artistes internationaux résidant en Belgique et de renforcer leur reconnaissance nationale et internationale. Suchan Kinoshita (Tokyo, 1960) vit et travaille à Bruxelles. Congrats to Suchan !

Olivier Foulon et Suchan Kinoshita sont les invités de la galerie Keijiban à Kanazawa. Exposition du 15 mars au 15 avril 2022, date à laquelle sera révélée en ligne l’édition produite pour cette exposition.

Le communiqué :

Keijiban is a limited-edition publisher and art showcase based in Kanazawa, Japan. It was launched by Olivier Mignon, founding member of the Belgian (SIC) platform and editorial manager of A/Rjournal. Keijiban works with significant artists living abroad to produce prints, multiples, and original works, which are launched through monthly exhibitions in a keijiban (掲示板), an outdoor community noticeboard. The editions are then sold online and shipped worldwide.

Suchan Kinoshita participe à l’exposition On Celestian Bodies au Centre d’art Arter à Istanbul. Commissaire : Kevser Güler. Jusqu’au 25 juillet 2021.

Drawn from the Arter Collection, the group exhibition titled On Celestial Bodies deals with questions around the possibility of reconceiving and reconstructing a vital terrain for living together in our present day. Including works by twenty-eight artists, the exhibition invites visitors to contemplate together the ways that beings come together and disperse, the manners through which they build relations, and their ways of distancing and converging with each other.

The title of the exhibition aims to point to the potentials and limits of the conception of the material embeddedness of beings. This notion of material embeddedness, as highlighted in the famous quote from the 1980s by astronomer and astrobiologist Carl Sagan, “We’re made of star stuff”, also informs one of the fundamental questions addressed in the exhibition: What would it mean to think of an artwork, a pencil, a human, a virus, a robot, a cat, a tree, a creek, a mountain as a celestial body as much as the Earth and Venus are? Dealing with the act of destabilising the foundations of anthropocentric hierarchies and exceptionalism, built, as they are, on binary oppositions, this question aims to debunk the validity of various dualities and distinctions, including those that place the human above the non-human.

With their proposals for, and criticism of, the complex and multiple ways of being together, On Celestial Bodies questions the possible effects that exhibitions and artworks may assume in imagining a politics of life. What are the potential ways of understanding art today as an act that cares for radical relationality, and one that affirms and defends life itself, in the context of the idea of justice, that makes living together possible?

[sociallinkz]

Risquons-Tout fait allusion au potentiel du risque en lien avec l’innovation. Comment quelque chose de nouveau ou d’inconnu peut-il émerger à une époque de plus en plus marquée par les processus numériques, notamment par des algorithmes de prédiction censés nous protéger contre l’incertitude et l’imprévisibilité ? Ces algorithmes façonnent les opinions et nous canalisent vers des bulles numériques où nous ne rencontrons que ce que nous connaissons et « aimons » déjà. L’influence croissante de l’intelligence artificielle s’accompagne d’une conformité grandissante de la pensée. Les artistes et les penseurs invités pour Risquons-Tout remettent ce phénomène en question en s’aventurant sur des territoires inconnus et inexplorés. L’exposition observe la manière dont l’innovation et la créativité peuvent émerger d’attitudes qui défient la norme. Le risque consiste alors à dépasser les frontières qui limitent la mobilité de la pensée, des idées ou des êtres humains à une époque où l’Internet offre potentiellement un accès illimité à toutes les connaissances humaines et non humaines.

Le titre de l’exposition est emprunté au nom d’un hameau sur la frontière franco- belge. Comme la plupart des régions frontalières, Risquons-Tout se caractérise par une histoire de franchissement de limites, de rapprochement, de passage et de contrebande. La contrebande est une forme s’infiltration transculturelle qui échappe à la loi, un passage ou un déplacement non autorisé, une façon de rencontrer de nouveaux canons, des règles alternatives et des codes hybrides. L’exposition se lance dans la recherche d’un espace sans borne et de nouveaux modèles d’ouverture qui mènent à l’éclatement de nos bulles sécurisantes, et explore les dynamiques de transition, de mixité, de métissage et de créolisation qui se produisent dans des lieux intermédiaires tels que les zones frontalières. Elle présente les œuvres de 38 artistes d’origines diverses, tous liés à la région Eurocore qui englobe la Belgique et ses voisins immédiats. L’objectif est de briser les frontières qui limitent la pensée et l’action contemporaines, d’aller vers l’imprévisible et le non normatif comme catalyseurs d’imagination et d’idées.

S’appuyant sur sa formation musicale et théâtrale, Suchan Kinoshita s’est inspirée de la scénographie pour réaliser une structure ressemblant à un podium de défilé et composée de revêtements de sol de gymnases recyclés. Sur le modèle du théâtre japonais traditionnel Nô et de sa passerelle menant à la scène, Kinoshita crée un espace intermédiaire, un peu comme un pont ou un passage à niveau. En l’absence de tout public, elle a invité des artistes à explorer la passerelle et à interagir avec les objets tandis que différents types de caméras captaient leurs mouvements. Ce qui subsiste n’est autre qu’une image fantôme rémanente dans un espace liminal. (dans le guide du visiteur)

(…) L’Engawa, dans l’architecture traditionnelle japonaise, est une passerelle de bois, extérieure, un plancher surélevé, courant le long de la maison. C’est un lieu de passage, coiffé d’un toit pentu ; l’engawa module la relation entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur. On s’y arrête, on s’y assoit afin de contempler le jardin ou le paysage, on y médite. Je me rappelle l’Engawa que Suchan Kinoshita érigea pour l’exposition In ten minutes au Ludwig museum à Köln. Simple plancher légèrement surélevé, rythmé par ses pilotis, extrait du même parquet de gymnase, il divisait l’espace vibratoire de l’exposition, invitant le spectateur à s’y asseoir afin de contempler un champs d’aérolithes, les Isofollies de l’artiste, jardin ponctué des scories d’un temps pétrifié.

Ce concept de passerelle, de lieu de passage existe également dans l’organisation de la scène de Nô. L’accès à la scène se fait pour les acteurs par le hashigakari, passerelle étroite à gauche de la scène, dispositif adapté ensuite au kabuki en chemin des fleurs (hanamichi). Considéré comme partie intégrante de la scène, ce chemin est fermé côté coulisses par un rideau à cinq couleurs. Le rythme et la vitesse d’ouverture de ce rideau donnent au public des indications sur l’ambiance de la scène. À ce moment l’acteur encore invisible, effectue un hiraki vers le public, puis se remet face à la passerelle et commence son entrée. Ainsi, il est déjà en scène avant même d’apparaitre au public tandis que le personnage qu’il incarne se lance sur la longue passerelle. Assurément, le ponton de Suchan Kinoshita tient autant du Engawa que du Hashigakari.

A dessein, Suchan Kinoshita brouille régulièrement les frontières qui peuvent exister entre sphère privée, celle du temps de la méditation, de la concentration, et espace public ; elle est tant attentive à la contemplation qu’à l’action, à l’énoncé qu’à la traduction, à l’interprétation de celui-ci. Ainsi confond-elle également régulièrement les rôles qui animent le processus créatif, la diversité des espaces mis en jeu, les disciplines artistiques même, choisissant la position qui consiste à ne jamais dissimuler le processus mis en œuvre, mais plutôt à en affirmer le potentiel performatif, afin de créer de la pensée, et par ricochet de la pensée en d’autres lieux, là même où celle-ci échappera à son contrôle. Ce ponton est une œuvre en soi ; il a une indéniable puissance plastique. Il opère également comme dispositif, ce que Suchan Kinoshita appelle un « set », soit un lieu et un moment d’interaction, un protocole associant des instructions ou des exercices participatifs ou des invitations à l’improvisation. Cette fois, elle précise même qu’elle a agencé ce dispositif pour « une performance non annoncée ». Tout en haut des gradins, une série d’objets est disposée sur des étagères. Ils sont en attente d’une performance, d’un performer. Suchan Kinoshita a décidé du protocole : il s’agira de déambuler sur cette scène – passage avec l’un de ces objets. L’œuvre s’appelle « Suchkino », une appellation qui touche à l’imaginaire, comme une contraction de son prénom et de son patronyme, comme un set linguistique également, entre la racine grecque « kiné » qui évoque le mouvement, le déterminant anglais « such », un tel mouvement ou le verbe allemand « suchen », chercher le mouvement.

Suchan Kinoshita s’adresse tant au performer attendu qu’au regardeur potentiel. Je repense à Jacques Rancière qui, dans l’Emancipation du Spectateur, écrit : « Il y a partout des points de départ, des croisements et des nœuds qui nous permettent d’apprendre quelque chose de neuf si nous récusons premièrement la distance radicale, deuxièmement la distribution des rôles, troisièmement les frontières entre les territoires ». C’est bien là que réside la position de Suchan Kinoshita. « Ce que nos performances vérifient, écrit également Rancière, – qu’il s’agisse d’enseigner ou de jouer, de parler, d’écrire, de faire de l’art ou de le regarder, n’est pas notre participation à un pouvoir incarné dans la communauté. C’est la capacité des anonymes, la capacité qui fait chacun(e) égal(e) à tout(e) autre. ». Au-delà même de l’imagination que chacun développera en toute autonomie.

J’ai vu, lors du vernissage de l’exposition un jeune performer, Simon Brus, s’emparer d’un objet cruciforme d’abord, d’une chaise ensuite. La chorégraphie qu’il improvisa sur l’étroite scène du « Suchkino » fut longue et singulière, intérieure, comme une conscience du corps, tantôt arrêté, tantôt en mouvement. Sortant de l’auditorium, j’ai découvert deux écrans. De petites caméras de surveillance sont fixées sur certains pilotis. Elles enregistrent et diffusent dans les sas de l’auditorium des fragments de temps et d’espace du « Suchkino ». Sur les écrans, apparaissent des images saccadées qui sont déjà une autre réalité. (JMB, 2012)

[sociallinkz]