In response to administrative difficulties when applying for a residential permit for a building that was originally a coach house, then a warehouse for glass objects from Czech Republic and is now her studio, Suchan Kinoshita has decided she does not want to be housed any longer: wohnen.

Anyone who reads the ‘Ministerial Decree of the Brussels-Capital Government of 23 January 2014, published in the Belgian Official Gazette of 07.02.2014’, with its definitions and specifications of housing and what criteria a residence must meet, will become discouraged indeed. Rules like “Each room is fitted with a light point with switch” are just the tip of the iceberg. The house must be divided entirely in compartments, and every space must meet standards specific to the room in question. This impacts the use of the spaces: the interpretation of inhabiting a space is strictly speaking no longer free. Activities like cooking, eating, sleeping, working, doing the laundry,… require separate zones (whether walled or not).

To what extent is there still a connection with the original meaning of ‘to be housed’, ‘to inhabit’ (‘wonen’)? The Germanic root WEN and the Sanskrit VAN (see also the Latin Venus) signify ‘to like’, ‘to love’. Through the Old Norwegian ‘una’ and the Gothic ‘wunan’, which means ‘to rejoice oneself’, cf. German ‘Wonne’ (=joy, bliss), and the Old-Irish ‘fonn’ (meaning ‘joy’; think ‘fun’) the sounds developped into the Middle Dutch word ‘wonen’ and the New High Germanic ‘wohnen’. So the basic meaning is: to enjoy being somewhere. The Indo-Germanic root WEN developped into (gi-)wuna in the West-Germanic languages, meaning ‘to accustom oneself’ (‘gewennen’), ‘habit’ (‘gewoonte’). In other words, ‘wonen’, to inhabit or be housed, is directly associated with a positive aspect of life.

Can people withdraw from inhabiting, ‘wonen’ in our society? It is claimed that this is impossible. One cannot not inhabit a residence. Because of this evident nature, inhabiting a space is given an existential dimension.

That is how German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) saw it as well. To him, to inhabit, wohnen, is our fundamental condition here on earth. In his essay Bauen, Wohnen, Denken (1951) he argues that wohnen is our way of being; it is the only way man can be on earth. Heidegger derives this meaning from the Old High Germanic word ‘buan’ that to him simultaneously means ‘to build’, ‘to inhabit’ and ‘I am’. In other words: I inhabit, therefore I am. Or vice versa.

In 1951, Heidegger gave a lecture in which he said that there is a crisis in Wohnen. He argued it does not result from a post-war housing shortage, or inadequate construction techniques, but because of a lack of insight into the essence of what housing is. Since the nineteenth century, man has been at home everywhere and nowhere. The spiritual connection to the place where people live has been lost. Man only has an instrumental attitude towards the world, usefulness and efficiency predominate. This applies to wohnen as well. In other words, the fact that people own a house does not imply they actually inhabit it.

We all know the snail and the turtle that live, work and sleep at the same place. For them, this constitutes a whole. There’s no nest to leave (or return to), no place for rest, no shelter or place to hibernate. Since they always carry their home with them when ‘at work’, the distinction between the two is blurred. Whether they are working at home or living at work is no longer relevant, home and work cannot but coincide. In that sense, they are continuously at work.

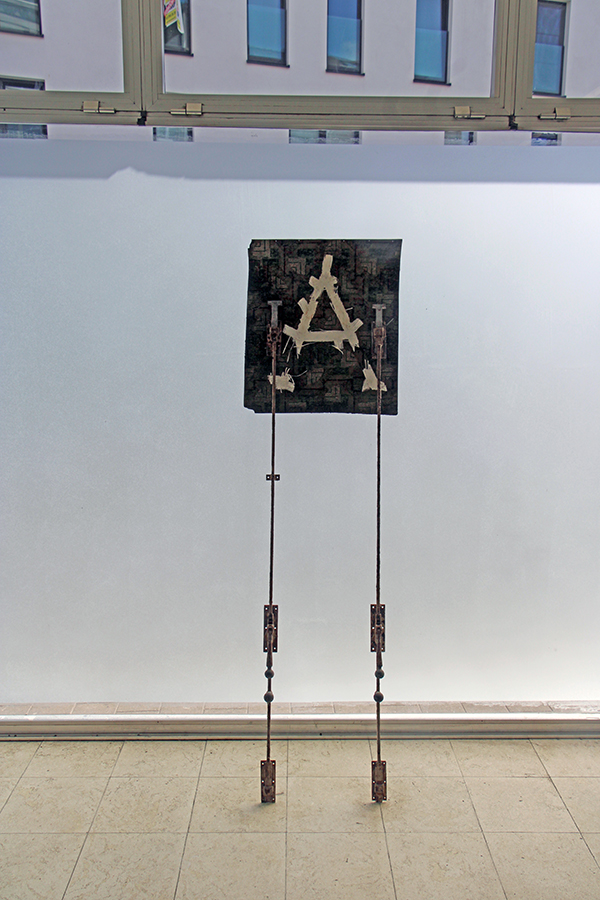

For Suchan Kinoshita, work and wonen are one. Piece by piece the exhibition reveals the history of her new building. She discovered new materials (like pitch in an underground reservoir, iron armatures in the side wall, old beams under the roof) at the site and she uses them to reshape spaces here. Five old armatures, externally bent to form a letter, used to support the side walls. Four of the five letters O – S – C – A – (R) were still present in the facade when Kinoshita acquired the building. She changed their order to C A O S (“chaos”).

This is where the anatomy of housing, das A und O vom wohnen, starts. Alpha and omega. New zones are created in the exhibition space through minimalistic changes.

Everything the building of Suchan Kinoshita has yielded so far constitutes the background on which the exhibition develops. Both specific elements and materials, and mental processes: How to relate to an existing situation? Because the space of LLS Paleis is not finished yet either, it presents new accents with every new exhibition.

One room of the house in Brussels has its own specific character, the ‘hanare’. It is situated underneath the ridge of the roof, with only a steep staircase leading to it. In Japan, a hanare is a separate place next to main house. It is a place where one can distance oneself from daily life. This is what happens in the last space: it has two chairs and a picture “Le Jardin Japonais” (which actually represents a Chinese table), in which seated figures look at a fictional model representing wonen…

Stella Lohaus, August 2018

Suchan Kinoshita

CAOS zonder R, 2018

mixed media

[sociallinkz]