Emilio López-Menchero

Vu Cumpra ? 1999

Vidéo, couleurs, 4:3, son, 00 :16 :04. Edition 5/5

It was in Venice, during the 1970s, that the first street hawkers appeared – mostly immigrants from French-speaking North Africa. Their entreaty ‘Vous, compra?’, a mixture of French and Italian, and a contraction of the Italian Vuoi comprare (Do you want to buy?) has since passed into common parlance: they are now called ‘Vucumpràs’. After them came sellers from sub-Saharan Africa – first from Senegal, and more recently from Eritrea and various English-speaking countries. The latest illegal hawkers to arrive are from Pakistan. Each ethnic group offers different products to the tourists scurrying by: the Pakistanis sell flowers and so-called ‘love locks’, while the Africans have come to specialise in counterfeit goods. This phenomenon, as we know, has since spread all over the world. In Paris recently, 103,000 metal statuettes of the Eiffel Tower, weighing over 19 tonnes, were seized from a pharmacy run by two Chinese people. They were supplying 150 street hawkers every day, raking in €10,000 a week from the proceeds. These Eiffel Tower sellers reminded me of a strange hawker I saw in Venice in 1999, at the Biennale preview for arts professionals. He was surreptitiously trying to peddle miniature replicas of the Brussels Atomium for a few lire to art lovers and collectors from all over the world, museum directors, tourists and onlookers. This performance by Emilio López-Menchero (who else would try and sweet-talk people like that?) reminds me of David Hammons’ Blizaard Ball Sale. In New York, during the winter of 1983, Hammons found a spot among the hawkers in Cooper Square and tried to sell snowballs arranged in order of diameter (from XS to XL) to passers-by. Placing a value on these ephemeral works which would ultimately melt, Hammons was flirting with the illicit, questioning the art market and drawing attention to the poverty suffered by a section of the New York population. As for Vucumprà? (1999), I believe it perfectly exemplifies all of Emilio López-Menchero’s work. Perpetually exploring identity, he too raises questions about the role and place of the artist in society. Infiltrating the ‘official’ art world – because he was certainly not officially invited to the Biennale – he leeches off it, asserts its composite origin, evokes immigration and exclusion, blends into the urban environment whose social symptoms he is analysing, and gets carried away. From his hawker’s bag he produces a vulgar tourist souvenir which is completely out of place in the setting of the Venetian Republic: a model of the Atomium, a symbol of Belgium, of the lost ‘30 glorious years’, of modernity… a work of art and an iconic image of science, even though everyone forgets that it was a collaborative work, designed by the engineer André Waterkeyn and built by the architects André and Jean Polak. Emilio López-Menchero is an architect too. He is non-practising, but regards urban public space as a critical space: he infiltrates it and works with it, whether he’s invited or not.

Emilio López-Menchero

Torero torpédo, col d’Aubisque, 2008

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 120 x 100 cm. Edition 5/5

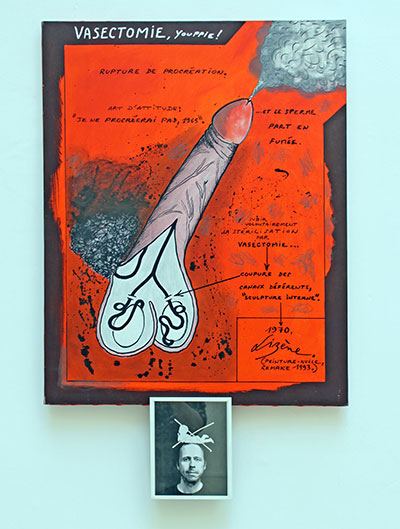

Born in Belgium to Spanish parents, when he gets on his Torero / Torpedo bike, wearing his dazzling toreador outfit, hands firmly clasped around its sharp horns, he is a hybrid of Eddy Merckx and Manolete, paying homage to Picasso. During the summer of 2008, this performance took him to the summit of the Col d’Aubisque, which deserves commendation, to a Paso Doble soundtrack. The body and its emancipation, starting with his own, has always been a central preoccupation for him… Whether it’s turning himself into a waddling sumo wrestler, in a magnificent battle against his own reflection in a mirror (Ego Sumo, 2003); or, a few days before delivering a project, paralysed by stress and doubt, unable to talk and his head about to explode, getting the idea to put on a bearskin hat and the uniform of a Buckingham Palace guardsman and stand outside Les Halles de Schaerbeek in Brussels (Garde de Schaerbeekingham, 2010); or exhibiting himself nude, standing on a round table, portraying the statue of Balzac undressed by Rodin (Trying to be Balzac, 2002). We have even seen him several times doing a tap dance (and of course he knows how to work with his hands too), sitting bare-chested on a stool, with headphones on, clicking his fingers and stamping his heels to the music of ‘Camarón de la Isla’. The audience can’t hear the music, while the artist can’t even hear the sound he is making: the performance is quasi-autistic (Claquettes, 2010). This question of the emancipation of the body – and the mind – led him to critically reconsider the work of the architect and theorist Ernst Neufert, author of the famous Bauentwurfslehre (Architects’ Data): first published in 1936 in Berlin, it is the architect’s bible, setting out a methodological basis for spatial measurements, standards and requirements, and is still used by many today. The perfectly standardised outlines in Neufert’s domestic and vernacular drawings have long been present in Emilio López-Menchero’s paintings and drawings. The artist also readily cites another architect, Hans Hollein, and his 1968 manifesto Alles ist Architektur. Indeed, everything is architecture, including the construction of self.

Emilio López-Menchero

Ego Sumo (2), 2005

Vidéo, couleurs, 4:3, son, 00 :05 :03. Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Balzac, 2002

Vidéo, N.B. 4 :3, son, 00:06 :38. Edition 5/5

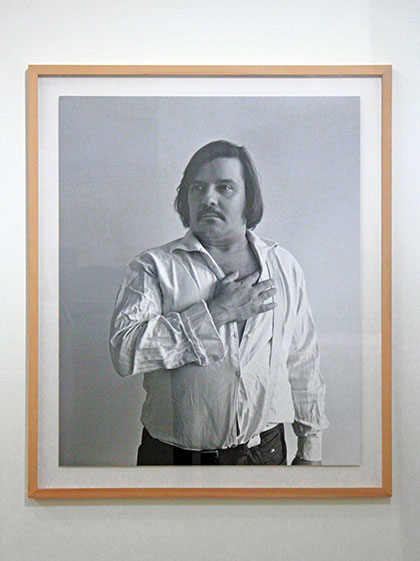

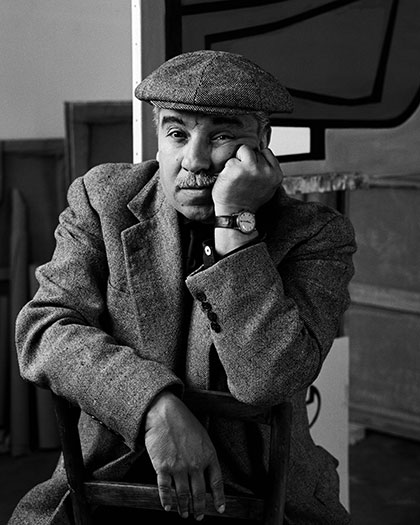

Since the early 2000s, Emilio López-Menchero has been regularly trying out different incarnations: appropriating the fascinating gaze of Pablo Picasso (2000); inhabiting Rrose Selavy (2005); substituting himself for Harald Szemann (2007); incarnating Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame, Russell Means style (2005); laying bare Rodin’s Monument to Balzac (2002); changing sex and composing a Frida Kahlo with herself as the subject (2005); taking on Rasputin’s hieratic pose (2007); conquering the Christ-like face of Che Guevara (2001); wearing Arafat’s keffiyeh (2009); turning himself into Carlos the Jackal, terrorist and master of cunning and disguise (2010); posing like Fernand Léger (2014), who also swapped the architect’s drawing pen for the painter’s brush. What motivated Emilio López-Menchero to attempt these successive incarnations, some 20 in all? After he shot his self-portrait of Pablo Picasso bare-chested in boxer shorts (2000), based on a photograph taken in the artist’s studio in Rue Schoelcher in 1915 or 1916, he said that the challenge was all about recreating this photographic self-celebration, of both his body and his artistic genius, which is something Picasso did regularly. The aim was not to create a pastiche of the photograph, or to imitate Picasso, but to incarnate both this ‘painter being’ and the archetype of the virile, macho Spaniard. Through these references, the artist initiates a process of reflexivity and recreation, mixing the familiar and the unfamiliar, recognition and surprise, erudition and facetiousness. A somewhat eccentric, even extravagant transformer, while changing his identity, López-Menchero finds his own. ‘Being an artist,’ he says, ‘is a way of expressing your identity; it’s the act of constantly inventing yourself.’ Each piece is unique, each Trying to be (the title of the series) is a specific adventure, an existential construction composed of autobiographical elements, references to other artworks, self-depiction, and a reflection upon the signals given out by the icon he has envisaged in detail. Ultimately it is self-construction via a continuous reflection on identity and its hybridities, exploring certain myths, their lies and their truths. The artist offers up a combination of exposure, disguise and domestic heroism. ‘Every true artist is a naive hero,’ wrote Émile Verhaeren of James Ensor, whose portrait in a woman’s hat with flowers and feathers Emilio López-Menchero revisited (2010). A naive hero is exactly what he is. On this topic I am reminded of the letter André Cadere wrote to Yvon Lambert in 1978, just before his death: ‘I would also like to say about my work and its multiple realities that there is another fact: the hero. You could say that the hero is in the midst of people, among the crowd, on the pavement. He is a man exactly like any other. But he has a conscience, maybe a way of seeing that, somehow or other, allows things to come to the fore, almost through a sort of innocence.’ This is a very accurate definition of artistic practice: it applies just as much to Emilio López-Menchero who, moreover, incarnated André Cadere (2013), carrying on his shoulder one of the Romanian artist’s round bars of wood, inspired by a now famous photograph taken by Bernard Bourgeaud in 1974. I would add that heroism can indeed be domestic: proof of this lies in the film that Emilio López-Menchero called Lundi de Pâques (Easter Monday, 2007), a ‘making of’ video of his Trying to be John Lennon, inspired by the Let it Be album cover. This film, made with a low budget, which gives it an undeniable intimacy, is a long series of almost pathetic attempts to pose as and inhabit Lennon in a private, homely setting that is strikingly realistic. Here, Trying to be becomes LET ME BE, while Easter Monday is an unusual day, a day, a new day, a regenerative metamorphosis.

Emilio López-Menchero

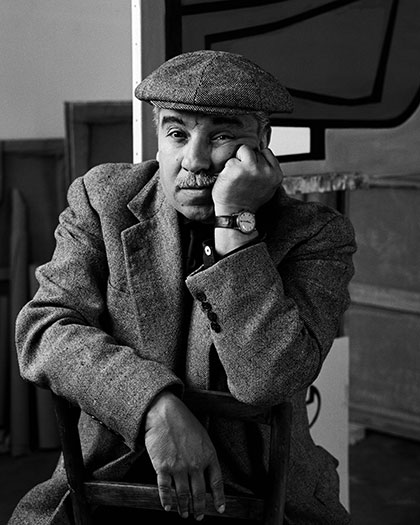

Trying to be Fernand Léger, 2014

Photographie NB marouflée sur aluminium, 110 x 88 cm. Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Cadere, de face (avec barre index 04 codes B 12003000, d’après « André Cadere, 1974 » », de B.Bourgeaud), 2013

Photographie N.B marouflée sur aluminium, 130 x 110 cm. Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero simply had to appropriate Man Ray’s famous photo of Marcel Duchamp dressed as a woman – the identity photo of Rrose Selavy, ‘stuck up and disappointing’, the artist’s ‘alter ego’, Duchamp’s ‘Ready Maid’. Trying to be Rrose Selavy (2005) is the archetype of the genre, in this case a change of gender. Similarly, it was in some way expected, or understood, that he would also incarnate Cindy Sherman (2009). Since her earliest works over 30 years ago, the American artist has almost exclusively used herself as her model and the basis for her compositions. Examining identity, a frenetic need to reproduce her ‘me’, her work represents the ultimate challenge of deconstructing genres, using farce, theatrics and hybridisation. Emilio López-Menchero chose one of Cindy Sherman’s Centerfolds from 1981. These horizontal images, like the double-page spreads in fashion and girly magazines, were commissioned by Artforum but never published, because the editor of the famous art journal believed they reaffirmed too many sexist stereotypes. The American artist – and therefore Emilio López-Menchero as well – is depicted as a vulnerable, fragile woman with no means of escape, held captive by the gaze of others.

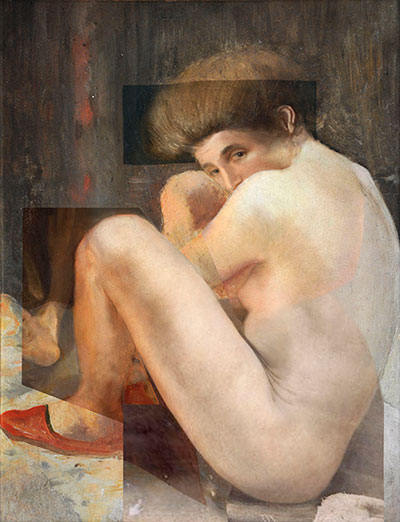

Like Cindy Sherman, the Trying to be compositions are mostly photographs rather than videos. Emilio López-Menchero transforms himself with make-up, costumes and accessories. He carefully monitors every aspect of the process, down to the tiniest detail. But the most important thing is the pose – to make his pose as close as possible to the icon he is referencing, but while completely reappropriating it in his own personal way. Mostly, these transformations are based on documentary research, which often guides the process of (re)creation. For example, in the portrait of Balzac in braces – photographed by Bisson in 1842 and owned by Nadar – the Napoleon of the arts has his hand on his heart. When the artist discovered it, the chance of possibly being able to reproduce his physiognomy was what motivated him. At the same time, he was looking at photos of Rodin’s Monument to Balzac taken by Edward Steichen, and various preparatory studies made by Rodin, which led him to the sculpture of Balzac itself. In fact, this duplication, of the sculpture and its photographic avatars, and of the physiognomy of Balzac and the work by Rodin, condenses the process of incarnation he is undertaking. That process ended up as the exhibitionist work that lays bare not only Rodin’s magnificent sculptural gesture, but the artist’s body as well. Exhibiting nudity and virility, López-Menchero strips back the process of synthesis conducted by Rodin, who sculpted the author’s naked body before covering it with a monk’s cowl. He is now as authentically Balzac as Rodin’s sculpture.

To personify Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, he does not choose one of her numerous self-portraits; instead he uses a photograph by Nickolas Muray, entitled Frida on White Bench, taken in 1938, which is both a frontal portrait and a composition. It is the political and cultural manifesto for an autonomous Mexican culture that interests Emilio López-Menchero. The intimate, the artistic, and social and political engagement transfigure Frida, who said that she often painted portraits of herself because she was the person she knew the best. When it was recently suggested to him that he incarnate Fernand Léger, he set his sights on a photo taken in 1950 by Ida Kar, a Russian photographer of Armenian heritage, who lived in Paris and London. Ida Kar took numerous portraits of artists and writers, including Henry Moore, Georges Braque, Gino Severini, Bridget Riley, Iris Murdoch and Jean-Paul Sartre. With a cap jammed on his head, and a salt-and-pepper moustache, Emilio López-Menchero stares down the lens, sitting astride a chair, his elbow resting on its back – a pose that Fernand Léger liked to assume. Reinhart Wolff and Christer Strömholm photographed him in the same pose. Once again, as in many of his Trying to be portraits, Emilio López-Menchero seeks to capture Fernand Léger’s gaze – a gaze full of curiosity for all forms of modernity.

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Ensor, 2010.

Concept & performance : Emilio López-Menchero, photo : Emilio López-Menchero & Carmel Peritore. Costume et maquillage : Carmel Peritore.

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 76,5 x 61,5 cm. Edition 10/10

Emilio López-Menchero

Autoportrait adolescent de mon éblouissement jaloux et de mon ébahissement illimité face à l’Histoire de la Peinture ! 2011

Vidéo HD, 16 :9, son, couleurs

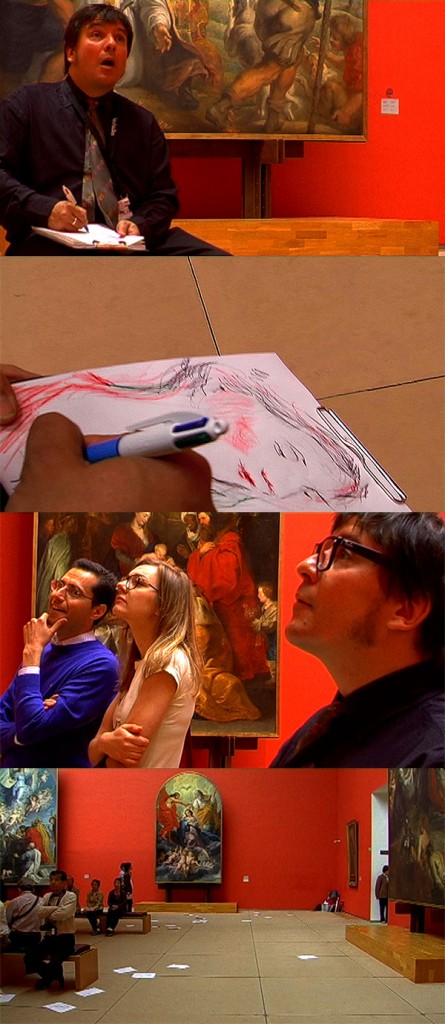

Within this series of portraits – these self-portraits, these reiterated attempts to put himself inside the mind of the model – his Trying to be James Ensor (2010) occupies a unique place. Ensor painted images of himself throughout his career: he left behind over 100 self-portraits. ‘In his early paintings, he appeared young, dashing, full of hope and spirit, at times sad but still splendid,’ wrote Laurence Madeline. ‘Soon, however, he vented his rancour by subjecting his image to a number of metamorphoses. He became a May bug, he declared himself mad, he “skeletonised” himself. He identified himself with Christ, and then with a humble pickled herring. He caricatured himself, made himself look ridiculous… He was both puppet master and puppet, in comedies and tragedies.’ Among these self-portraits is one in a flowery hat from 1883–1888, in which James Ensor modelled himself on Peter Paul Rubens. James Ensor ironically swapped the master’s hat – with panache – for a woman’s hat with flowers and feathers. ‘In these times, when anyone is everyone, the poet, the painter, the sculptor and the musician is only worthwhile if he is authentically himself,’ Emile Verhaeren said of the baron from Ostend. This self-portrait in a woman’s hat is a sort of Trying to be avant la lettre: clearly, he could never have escaped the Emilio López-Menchero treatment. In the wake of this, a few months later he rushed into the Rubens room in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium and suggested doing a performance there, which he called, not without lyricism: Autoportrait adolescent de mon éblouissement jaloux et de mon ébahissement illimité face à l’Histoire de la Peinture ! (Teenage self-portrait of my jealous bedazzlement and my limitless amazement at the History of Painting! – 2011). The film that resulted from this act showed us the artist drawing, taking inspiration from the master’s paintings. Painting was his childhood fantasy: after a family visit to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, he made his father buy him tubes of paint immediately. Emilio López-Menchero was 15 at the time; he took refuge in the hotel so he could paint. He has continued to paint ever since. However, it was not until 2012 that he finally dared to show this side of his art to the public, with his first exhibition dedicated solely to painting.

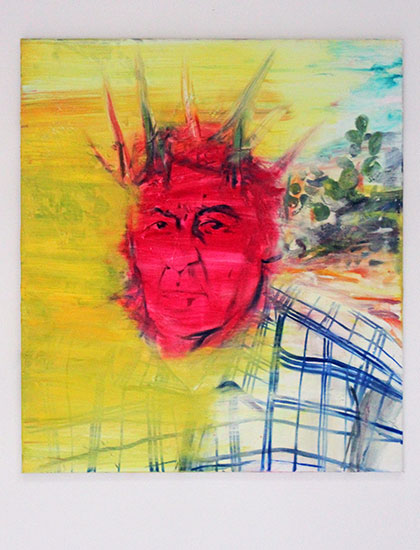

Works on display there included Gare au gorille! (Beware the gorilla!, 2011), in which a powerful, primitive, monumental King Kong seems to be bursting out of the canvas before a fragile Fay Wray, depicted as a tiny figure in a corner of the painting. Hanging next to it was a canvas of a much more modest size: a portrait of Tintin belching colour out of his mouth… not just any colours, but the colours of the Belgian flag. The title of the painting is Kuifje (2011). Further on, two soldiers, a hut, an urban background, part of an American banner, a history painting. Emilio López-Menchero has revisited his Checkpoint Charlie (2011) in painted form; the colours drip onto and spread across the façades. Then we have a very large-scale painting, to emphasise the height of the NYPD’s Skywatch – the telescopic mobile towers used by the New York police; here, one rises above a stretch of water (the Hudson perhaps), some wooden houses on the bank, and Tarzan and Jane, or rather Maureen O’Sullivan and Jonny Weissmuller, intertwined on the shore. Emilio López-Menchero painted this after a visit to New York. He spent a good deal of time walking along the Hudson Bay; he scrutinised the wooden houses on its banks, and he clearly observed these strange mobile towers beside Ground Zero (Miradores, 2012). These were all things that caught his eye and became some of his preoccupations. Emilio López-Menchero is perpetually interested in the icons of the last century, such as Jonny Weissmuller, who appears in this canvas as Tarzan, whose famous cry he borrowed, making it resonate from the top of eight towers in the town of Ghent, eight times a day for three months: an audio piece that turned the city into an urban jungle (Hey! Het is… Hum… Dinges… Hum… Tarzan! 2000). Or Tintin, another icon who is called Kuifje in Dutch, belching out the national languages of Belgium. Or the Michelin man, inflated and up in the air in the painting entitled Le Cahier, El Cuaderno (2012). Or Russell Means, leader of the Lakota Oglaia – Sitting Bull’s tribe – who appeared in the film The Last of the Mohicans, was painted by Andy Warhol, and with whom Emilio López-Menchero identified, paying homage here both to the Pope of Pop Art and the Native American chief (In Russell Means’ mind, 2011). Or the woman he calls Paki Beauty (2012), because she is the icon displayed in the Pakistani shop next to his studio. So Emilio López-Menchero’s painting, while asserting its autonomy, refers back to other past works or performances of his. Cienarga (2011), in which a cowboy who seems to have shot himself in the foot is shocked to see a geyser of mud rising out of the ground, takes us back to Once upon a Time (2002–2003), the project in which Emilio López-Menchero, playing the role of Charles Bronson, turned the centre of Courtrai into a town from a western, through sound and images. It’s true that Courtrai did have its own ‘gold rush’ and is regarded as the Texas of Flanders. When he painted Chinatown (2012), which shows a giant, festive carnival mask against a backdrop of a town and a row of tower blocks, among the compact crowd he placed two sumo wrestlers, referring back to Ego Sumo. Emilio López-Menchero paints his own world, the things that feed his imagination, continuously fusing situations, painting the things he observes, which then rise up like a memory or a film in which the shots follow one after another and overlap. His painting is gushing, urgent, jubilant; it constructs and deconstructs, freeing itself from the image. From this festive scene, celebrating the year of the Dragon, all that is left are the dancing, nylon-stockinged legs, the high heels of the majorettes – Peruvian, Bolivian or Colombian, I forget which, but it doesn’t matter. The rest of the canvas is just the joy of these ladies’ skirts, in which appear two pairs of stunned, astonished eyes, and groups of silhouettes wearing the blue uniforms of the Chinese working classes. I also have to mention Térésa (2012), the powerful portrait of the artist’s sister; and Pater (2012), a portrait of his father, his head encircled in a crown of clothes pegs – an unexpected Trying to be with his father in the role of the Great Manitou. And the ball-shaped, almost transgender face, which he appropriately calls Autoportrait (Self-portrait – 2013).

Emilio Lopez-Menchero

Pater, 2012

Huile sur toile, 150 x 133 cm

Emilio López-Menchero, the ‘little Spaniard’ born in Mol, Limburg, describes himself as always between one and the other – l’entre-deux in French or tussen tussen in Dutch (2003). This is the title of one of his series of drawings, which has elements of both sketchpad and animated film about it: it is a long sequence of unexpected figures, a series of drawings where the agility and inventiveness of the line guides the metamorphic transitions from one icon to another. A multidisciplinary artist, he is continually straddling two media, two sketches, two projects, two images or two references. This is undoubtedly where his inventiveness springs from, where the imaginary lurks and his imagination develops. His numerous projects which, at first glance, seem heterogeneous, a response to specific or contextual situations, nevertheless echo each other, rebound off one another, enabling the viewer to read his works in a cross-referential way. So his three urban movement pieces, whether he is trying to be André Cadere with a bar of wood in his hand, trying to bring a 12-metre-long tube of polythene into a contemporary art fair, a bit like slipping a thread through the eye of a needle, or trying to orchestrate the moving of a railway track across town, it is always an attempt at collective resilience against some urban planning aberration. The common paradigm in these three works is the moving of a straight, very thin object, and the fact that they are part of a ritualistic performance. The first is a reflection on the icon, with André Cadere’s round bar of wood on his shoulder. Blending fiction with reality, archive, homage and interpretation, Emilio López-Menchero walks through the streets with a meditative air, carrying the long bar of wood on his shoulder, a flâneur who doesn’t care about the inevitable reactions of the public at this strange sight. It reminds me of the short black-and-white film made by Alain Fleischer in 1973, showing Cadere walking up and down the Boulevard des Gobelins in Paris. The second is a penetrating approach to a compact sociological space, re-evaluating art, monuments and the notion of work. Wearing protective helmets and workmen’s clothes, directed by foreman López-Menchero, 12 men carry a 12-metre-long tube through the narrow corridors of a contemporary art fair, before placing it on the grass, like a sculpture, opposite the entrance to the building. THE PIPE (2010) and its carriers are thus sizing up all things, including a social space. A homage to the reality of work, an enigmatic horizontal sculpture, this tube is thus given a monumental capacity for expression. The third is even stranger: in Brussels, the artist presents the moving of a single railway track on wheels, an 18-metre-long Vignole rail weighing one tonne, which he intends to move along the entire course of the North-South Junction – an incredibly controversial urban space. This junction solved a mobility problem, but at a price: the destruction of whole blocks of houses built in the 19th century in the purest Haussmann tradition. A contemporary ritual, the very idea of carrying this Rail (2013) in procession activates a will to resist this fault line, this urban scar – now a series of grand boulevards which, after nightfall, resemble an urban desert.

Of course we have Emilio López-Menchero to thank for the monumental megaphone close to Brussels South Station. Facing towards the station, this place of confluence, a reference to an episode in the Spanish Civil War, Pasionaria (2006) puts freedom of speech in material form. It is a homage to Dolorès Ibarruri, an inspirational Communist Party activist (López-Menchero’s grandparents were Spanish Republicans after all), and also refers to Joris Ivens’ 1937 film The Spanish Earth. It was a public commission destined for a multicultural environment, and dedicated to all migrants, in a site where social and political events regularly take place. Pasionaria is a relational space, as is Homme Bulle (2006), a sculpture of a modern man in a business suit, as anonymous as one of Neufert’s figures. There is a monumental speech bubble coming out of his mouth: round, blank, immaculate, a silent invitation. The sculpture is not an object to look at, but a situation to create. To be complete as an artwork, the spectator has to put the finishing touches to it. With a felt pen or a spray can. The sculpture is an open situation in a state of transition, where intersubjectivity becomes a mechanism for creation, and the procedural nature of its development turns the work into an event. Graffiti, tags and direct marks are all signs of contemporary urban culture; here, they help create a state of ‘being together’. Being artist and viewer together, being one-day-only graffiti artist and casual tagger together, gathered at the same bubble. Homme Bulle appeals to passers-by, offers them an escape from everything that is conformist, prescribed, recommended, correct or anonymous, for a moment of free expression. Self-construction is also achieved through otherness – that is certain. Hence, once again infiltrating the codes of popular culture, between 2010 and 2012 he produced a series of cinematographic portraits in two working-class districts of Ghent – Moscou and Bernadette. This project involved asking some 30 residents of these districts to sing a song in front of the camera. The films – all sensitive, modest portraits – were projected two at a time onto two screens, like a competition. While a resident of one district sang, a resident of the other district listened, and vice versa. The work created a rich dialogue, not only between the residents of the two districts, but between different generations, cultures and personalities (MOSCOU-BERNADETTE, 2012). The same thing happened when Emilio López-Menchero installed his Checkpoint Charlie (2010) in Brussels. He placed it on the site of what was once the Flanders Gate, exactly midway between a gentrified district, with its trendy bars, art galleries and fashion boutiques, and another district beyond the canal which has one of the highest density of immigrant populations in the capital – a migrant ghetto inhabited first by Pakistanis and then by Moroccans from the Rif region. The artist’s performance, in what looked almost like a film set, this recreation, this importing of Berlin’s historic Checkpoint Charlie, was clearly highlighting an urban divide, condensing economic, sociological and urban planning observations into a single work. And, as the film made during the event demonstrates, it is also an intervention in a real context, where the art is all about action, presence and immediate affirmation. Impeccably kitted out in an American army uniform, stopping pedestrians, cyclists and motorists with a military gesture, in a serious and remarkably natural way, Emilio López-Menchero questions, explains, opens dialogue and provokes a wide variety of reactions. Fiction is merged with reality; the Checkpoint Charlie device has become both a relational space and a place of conflict, condemning a problem that is far from a local, isolated situation.

Emilio López-Menchero

H2/H1, 2013

Technique mixte, dimensions variables. Installation Les Halles, Porrentruy (CH)

Emilio López-Menchero

Brugse Huis (part of Indonesie !), 2010

Technique mixte et dispositif sonore

Notions of borders, migration and immigration, exclusion and alienation are ever-present in the artist’s work. When he visited Hebron, Palestine’s second city, where some of the most extremist Jews in Israel, living there in a few tiny settlements, crystallise tensions – to such a degree that some IDF soldiers decided to break their silence – he reacted to what is euphemistically called ‘a principle of separation’. When he came back, he evoked the checkpoints with their chicanes, the partition of the Tomb of the Patriarchs, the deserted streets and the hundreds of shops closed by the army for ‘security reasons’. ‘I arrived in Hebron on a Friday,’ he says. ‘It’s the most interesting day of the week – a day of prayer for Muslims and the start of the Sabbath in the evening. So I was able to observe the absurdity of the situation around the Tomb of the Patriarchs. A single checkpoint filters the two monotheistic religions, revealing this system of theatre-like stage and wings where synagogue and mosque are separated only by a shared wall.’ However, what drew his attention were the nets strung above the alleyways, full of waste and rubbish, receptacles for every kind of filth – a makeshift apparatus placed there by the Palestinian population to protect themselves from the detritus thrown out of the windows by the Jewish settlers living above these alleyways. On his return, in various contemporary art spaces, Emilio López-Menchero hung nets identical to those in Hebron, threw all kinds of detritus in there, and invited the viewer to walk underneath them (H2-H1, 2013). I am reminded here of Jacques Rancière’s essay on the paradoxes of political art: ‘The problem,’ he writes, ‘does not lie in the moral or political validity of the message conveyed by the representative apparatus. It lies in the apparatus itself. Its fissure reveals that the efficacy of art does not consist in conveying messages, providing models or counter-models for behaviour, or learning to decode representations. First and foremost, it consists in the arrangement of bodies, the division of unique spaces and times which define ways of being together or apart, opposite or amid, inside or outside, close or distant.’ This is certainly the case here. Invited to Bruges in 2008, in the work Indonésie (2008), Emilio López-Menchero points out the contradiction between tourism and immigration, hospitality, mobility and detention centre. Here, he juxtaposes two imposing sculptures: a cloud of pillows and a traditional Bruges house with gables in the shape of staircases, with all the external signs of comfortable hotel hospitality. However, the house is a wire cage and from four loudspeakers come the sound of four women’s voices speaking with Chinese, Indian, Armenian and Guinean accents, reading out the different nationalities identified in the detention centre inside the city’s former women’s prison, which was initially intended for detaining illegal immigrants, then later for failed asylum seekers as well. The cloud of pillows is a memorial to the Nigerian asylum seeker Semira Adamou, who was suffocated to death at Brussels Airport during an attempt to expel her from Belgium. Viewers who stand in the centre of these feather pillows hear Liza Minnelli singing ‘Willkommen, Bienvenue, Welcome’, from the film Cabaret (1972) – a refrain on a loop, a stifled rendition of the same old song. M, le Géant (2007), a modern man with no face and a Neufert-like body, an anonymous, hypermodern man that one day Emilio López-Menchero introduced into a procession of historic and folklore giants, witnessed the whole thing. The artist even used him as a Trojan horse to get inside the former Bruges prison to meet illegal immigrants and failed asylum seekers. He is omnipresent in various forms in the artist’s oeuvre.

So the guiding thread throughout Emilio López-Menchero’s oeuvres is this quest for emancipation. Trying to be, trying to say, trying to do. He also emancipates himself from grand, solemn, ideological discourses. What counts is the configuration of the space he occupies, where he puts in place his unique strategies. The important thing is to find the right expression that translates both thought process and feeling; what motivates him is continual self-reinvention. Being an artist and being in the world are merged, as are being oneself or even being one’s alter ego – all of this after having completed a long process of testing. In the contemporary art world, we tend to take a certain model of efficacy for granted; persuasive force and financial power go hand-in-hand here. The notion of ‘trying to’ that punctuates Emilio López-Menchero’s artistic journey, and comes back again and again as a leitmotif, which we could also translate as I dare, I risk, I try, I feel, I probe, I identify, I measure or I embark, is all the more piquant for it – a first, and simultaneously last way of being oneself. It is undoubtedly effective. Emilio López-Menchero is successful in all of this.

Jean-Michel Botquin

[sociallinkz]